It has been surprising to me since moving to Japan six months ago to learn that very few hospitals and health systems are using Lean or the Toyota Production System principles in their operations. Japan is known for high quality clinical care, but from what I’ve heard these six months, there are many opportunities for improvement across the health delivery sector.

A few weeks ago, after my visit to the Toyota Kyushu plant, I had the opportunity to visit a Japanese hospital known for its application of Lean thinking and Total Quality Management. I was excited to see what they were doing, as it is rare to hear about Lean applied in healthcare in Japan.

Improvements through Lean and Kaizen

My host to this hospital has been the Director of the Kaizen Promotion Office (KPO) for the past two years. During her tenure, she has helped advance their application of Lean thinking in the hospital beyond its practice of TQM.

I appreciated the tour and seeing the great work my colleague is doing with their KPO and supporting kaizen and improvement the organization. They are leading the way for improvements in the Japanese health system.

While the application of lean hasn’t moved to a connected management system yet (such as through strategy deployment or linked checking), the KPO has created pockets of change that are laying the foundation for more improvements in years to come.

Hospital Overview

Aso Iizuka Hospital looks like any hospital you might picture – if you replaced the Japanese language signage, it could have been anywhere. There was a new wing, which felt very modern, connected to an older facility.

The hospital is one of the largest hospitals in the region, and is located in a semi-rural area in the southern part of Japan. It has roughly 1110 beds, with 36 departments, 275 physicians and 2300 employees.

Annually the hospital receives about 480,000 outpatients and 330,000 inpatients, and conducts about 5,400 surgeries.

Privately held – less common in Japan

Since my initial overview of the Japanese health system, I’ve learned that private organizations are not allowed to own or manage hospitals, except for those privately owned hospitals that were grandfathered in before the law regarding private ownership was put into place. Additionally, the law requires that the senior executive at a hospital be a physician.

About 30% of hospitals in Japan are privately held, with the remaining 70% managed by the government.

Improvement minded – Lean and TQM

The hospital I visited is well-known in Japan for the improvement work it has done for the past 25 years, primarily focused on Total Quality Management (TQM) Quality Circles. About 150 staff members in around 20 groups participate in TQM activities every year. In the past few years, it established the KPO to bring Lean thinking into its operations and hired my colleague to lead the team.

Relationship with global healthcare systems to learn

Aso Iizuka Hospital has a close relationship with Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle and conducts learning exchanges with Virginia Mason to learn about operations and improvement at both institutions. They host an annual process improvement summit that usually includes guest speakers from V.M.M.C.

In addition, they have relationships with several other hospitals and health systems in the U.S. and other countries to learn and improve their medial care.

Tour of the ORs

5S in the Operating Rooms

As part of my visit,I got sit in on a meeting (in Japanese – another opportunity to practice listening!) about follow-up from a 5S event related to their anesthesia supplies and operating rooms.

I learned during my tour that there are 17 operating rooms (including 3 for outpatient procedures), but there are only about 20-30 cases a day.

The KPO’s efforts with the anesthesia carts has resulted in decreased par level and amount of supplies needing to be stored, but other problems are now being made visible.

This is one of the powerful outcomes of applying Lean thinking and creating standard work – problems that were once visible now are surfaced, such as variation in ordering practices, duplication in supplies, and unclear restocking procedures.

This outcome is common and I’ve seen it in all organizations in which we’ve done Lean improvement work. The challenge is to not get discouraged! Kevin Meyer of Gemba Academy recently wrote a blog post that I enjoyed about this challenge that organizations face as they begin improvement activity.

Tour of patient care areas

In addition to seeing the 5S and improvement work that the KPO is actively working on in the ORs, I got to walk through several of the patient care areas.

Crowded waiting rooms

I don’t have any photos of the crowded waiting rooms as I wasn’t able to take pictures of patients, but I was astounded with the number of patients and family members waiting throughout the clinic areas.

I counted about 60 people waiting in the waiting room that covered the internal medicine and GI clinics! I was told that this is typical at Japanese hospitals and clinics – and that this hospital is considered one of the best.

Accessing the healthcare system in Japan

I learned something new about the Japanese system during this visit. In Japan, you don’t get an appointment for your first visit to a doctor. Instead, you go to the clinic (often located within the hospital) and show up with your issue, sort of like an urgent care.

Or if you have a referral by another physician and are able to get an appointment, you are given an appointment for a one hour block of time in which 20 other patients also have an appointment. I had heard of the “three minute appointment” but I hadn’t realized how this works in actuality.

Clinic schedules and workflow

Physicians at this hospital see about 30 patients a day, but this is primarily only in the morning. Since there are no hospitalists in the Japanese health system, physicians go out to the wards in the afternoon to check on their inpatients. Only one or two physicians stay in the clinic for the afternoon.

Also, physicians work in their own clinical rooms (occupying valuable clinical care real estate while they document or do other “office” work) and do all parts of the appointment themselves (from rooming the patient, taking vitals, etc).

In the picture to the left you can see these rooms – which serve essentially as the physician’s office and clinical area.

There are no medical assistants or nurses to help manage patient flow or assist with the appointment (though nurses help with doing injections and other aspects of clinical care) as we implemented at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation and that are used by other U.S. outpatient practices.

Lots of waiting!

As a result of theses factors, patients end up waiting for a long time. A usual wait for an initial appointment could be 1-2 hours, and this is after already having to wait to register upon arrival. This was the burning platform for the improvement work that my colleague initiated when she joined the KPO.

Value stream kaizen improved patient wait time

My colleague shared that as a result of intensive value stream work over the past two years,they have seen a huge reduction in wait time in the General Medicine clinic. Over a series of four focused kaizen events, they were able to reduce patient wait time from 80 minutes to 30 minutes. They continue to work on improving the times further.

The proof-of-concept in General Medicine has created pull by some other clinical areas, and three departments this year have requested the help of the KPO – including requests by physicians.

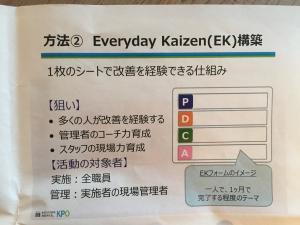

Everyday Kaizen to bring improvement thinking to the frontline

In addition to supporting kaizen events, the KPO has established “Everyday Kaizen” as a method to spread PDCS thinking to the front line. Staff can fill out a small form following the steps of Plan Do Check Act.

Everyday Kaizen is similar to the kaizen approach that I’ve described used by some Japanese manufacturing organizations or by hospitals that I’ve worked with.

They had about 100 ideas submitted by staff in over 20 departments in the first three months of introducing Everyday Kaizen.

Japan’s healthcare opportunity

There is a huge opportunity in Japan to bring more Lean thinking and improvement into its hospitals and health systems. Given the number of companies in Japan who have been applying Lean thinking for decades, the Japanese health system may be served by going to some other industries in their backyards to learn about Lean management, or to establish learning relationships with hospitals in other countries (like this hospital does) to learn how they are applying Lean in a healthcare setting.

Mark Graban has made a similar observation in his visits to Japan that it is rare to see health systems applying Lean thinking.

This is further evidence to me that Lean and the Toyota Production System are not inherently easy concepts to apply for anyone – including the Japanese.

I am giving a talk about Lean and healthcare for aJapanese company that wants to learn more about how to manage hospital operations this week. I will be interested in getting their perspective about healthcare and Lean in Japan, and sharing my experiences in supporting improvements in U.S. and Australian healthcare systems.

What is your reaction?

Are you surprised that Lean/TPS is not used by healthcare organizations in Japan?

If you have lived in or visited Japan, what is your experience?

Please share your comments and experiences below.