The Gaps in Lean Implementation

“Lean has failed.”

That’s the bold statement James Womack—founder of the Lean Enterprise Institute and MIT researcher whose team introduced the term “lean” to the world—made at a conference where we both recently spoke.

It’s a comment that’s stuck with me.

Has lean really failed?

And, if so, what can we do to course correct?

To explore his statement I invited James Womack to Chain of Learning, to share his reflections and experiences over the past 40 years—where his vision for lean management has fallen short, where it’s succeeded, and what we can learn for the future.

In this episode, we take a hard look at lean’s evolution, from James’ original vision following the publication of “The Machine that Changed the World” nearly 4 decades ago to its real-world impact today.

(…and don’t miss Part 2 of this conversation where Jim Womack and I explore lean’s future, its relevance for today’s global lean community, and his advice for the next generation of leaders.)

In this episode you’ll learn:

✅ The five critical interlocking elements of successful lean enterprise transformations — and what’s missing

✅ How to build systems and practices to sustain a lean culture that truly supports frontline teams

✅ Why most companies get their approach to operational excellence backwards and the challenge of getting leaders to see lean principles as the key to getting results

✅ Why off-shoring and out-sourcing aren’t long-term solutions

✅ The biggest challenges leaders face with lean transformation

Listen Now to Chain of Learning!

Tune in for powerful stories and insights from one of the founders of the lean movement, and a chance to rethink what’s next for lean leadership and how you can adjust your approach towards organizational transformation.

Watch the Episode

Watch the full conversation between me and James Womack on YouTube.

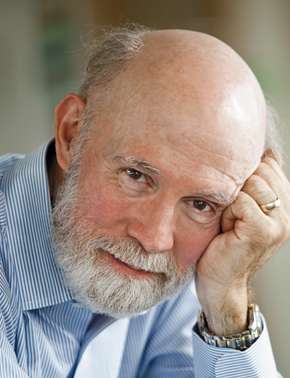

About James (Jim) Womack

About James (Jim) Womack

James P. Womack, PhD, is the former research director of MIT’s International Motor Vehicle Program who led the team that coined the term “lean production” to describe the Toyota Production System. Along with Daniel Jones, he co-authored “The Machine That Changed the World”, “Lean Thinking”, and “Lean Solutions”.

I recommend “The Machine That Changed the World” among my 10 top books on Lean Management and Lean Production.

James is the founder of Lean Enterprise Institute where he continues to serve as a senior advisor.

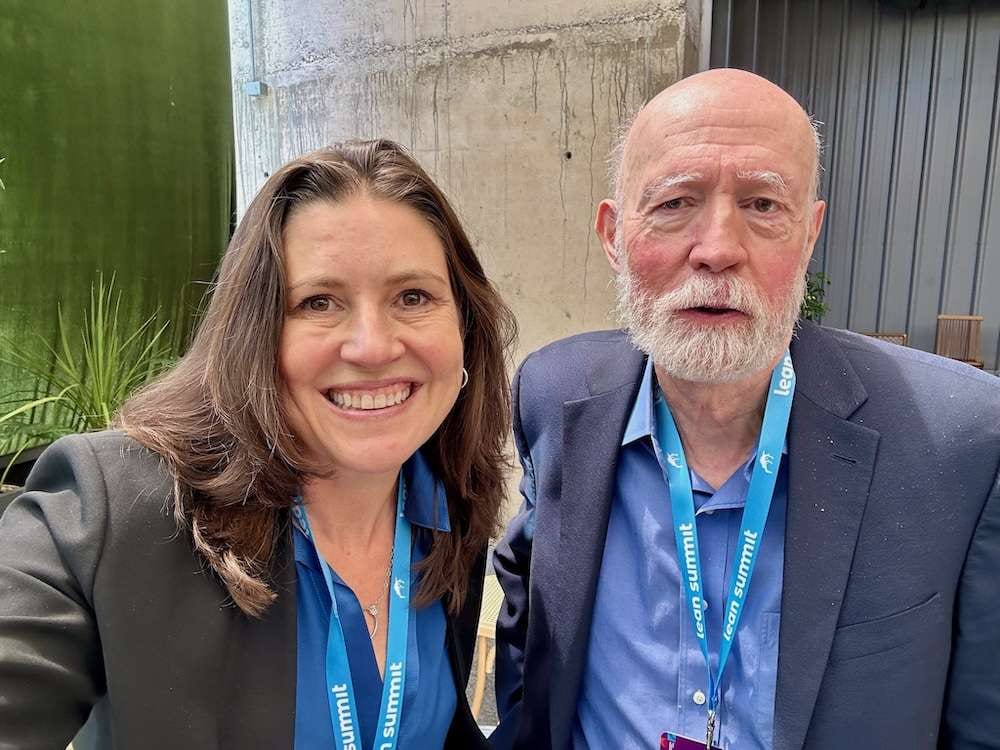

I first met James (or “Jim” as I call him) nearly 15 years ago when we were both speaking at a lean conference in Australia. Since then, our paths have crossed many times, most recently in Santiago, Chile, where we spent time digging into the history and future of lean.

He has also endorsed my book Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn:

“Katie explains how Yoshino found his North Star, overcame adversity, framed situations in a positive way, learned from failure, and always developed the people he worked with as well as himself. If you reflect on and heed its wisdom, you will become a better person, and a better coach and manager. A gift to treasure in a dark time.” — James P. Womack

Reflect and Take Action

Has Lean really failed?

Or have you just missed the mark in how you apply it?

As James Womack shared, too many organizations treat lean and lean implementation as a set of production and manufacturing tools rather than the management systems, product and process development, or supplier relationships.

Short-term thinking, leadership turnover, and outsourcing lean efforts have only made it harder to sustain real transformation.

So, let’s pause and reflect:

- Where has Lean fallen short in your experience?

- What’s actually working in your organization?

- What adjustments can you make—individually and as a community—to bring lean closer to its true potential?

Lean is all about continuous learning and improvement—so let’s apply that thinking to lean itself. Using the Plan-Do-Check-Adjust (PDCA) cycle, how can you refine your approach to lean implementation?

Take a moment to think about James’ insights—and your own experiences—and let’s figure out what’s next for lean together.

Important Links

- Connect with James Womack

- Listen to Part 2 where the future of lean is headed: Episode 38 | What’s the Future of Lean? with James Womack

- Check out my website for resources and working together

- Follow me on LinkedIn

- Listen to the discussion with Jim Womack, Jamie V Parker, Mark Graban and myself where we discussed the GE Lean Mindset Event

- Read my blog on highlights from GE’s “The Lean Mindset”

Listen and Subscribe Now to Chain of Learning

Listen now on your favorite podcast players such as Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Audible. You can also listen to the audio of this episode on YouTube.

Timestamps:

02:41 – Jim Womack’s vision of what lean’s impact would be today

03:22 – Theories of why Japanese companies were steadily taking over American and European companies

07:25 – The five interlocking pieces of lean transformation and what has been missed

07:49 – The misconception of Kaizen

14:27 – Challenges in sustaining lean practices and lean implementation

15:01 – Management’s role in implementing lean principles

19:00 – What lean leadership could have looked like if implemented the right way

21:58 – The impact of offshoring and outsourcing

24:29 – Barriers to senior management buy-in

26:42 – Challenges in the frontline healthcare system and how they can improve

30:27 – The importance of daily management and Kaizen

32:41 – The success story of GE Appliance’s lean transformation

37:46 – Two contributions to GE Appliance’s success

39:28 – The meaning of constancy of purpose

41:04 – Importance of knowing your north star

41:55 – The creation of Hoshin planning and why it fails the first year

43:54 – How we get out of the short-term approach

Full Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Jim: I said, uh, here in 45 years, we have failed to create real lean enterprises almost anywhere. I didn’t say we’ve done nothing. I said, uh, compared to what I had hoped, I, this was a realized a high mountain. But I wanted to get all the way to the top of that mountain and we have not gotten there.

[00:00:19] Katie: Welcome to Chain of Learning, where the links of leadership in Learning Unite.

[00:00:23] This is your connection for actionable strategies and practices to empower you to build a people-centered learning culture, get results, and expand your impact so that you and your team can leave a lasting legacy. I’m your host and fellow learning enthusiast, Katie Anderson. Leans failed. That’s the provocative comment that James Womack, one of the key founders of the lean movement declared to the audience at the lean summit in Santiago, Chile at the end of 2024.

[00:00:51] And it’s a comment that has stuck with me over the last few months, Jim, the MIT researcher whose team coined the term. Lean back in 1990 with the release of the seminal book, The Machine That Changed the World, and the founder of the Lean Enterprise Institute believes that Lean has failed to reach his vision for its potential.

[00:01:10] I’ve known Jim personally for nearly 15 years. When we first met. As international guest speakers at a lean conference in Australia. And recently we spent time together in Santiago, Chile, where we explored the history and future of lean over meals. And in a panel discussion, following our keynotes at the event, I invited him to the podcast so he could share his reflections and advice with you too.

[00:01:31] As we look at the future of lean has lean thinking and practice really failed. And what’s the future of lean for those of us passionate about its potential? As Toyota leader Isao Yoshino has shared with me, and I highlight in my book, Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn, failure is only failure if you don’t learn something from it.

[00:01:50] Jim’s and my conversation spanned over an hour and a half as he reflected on my questions and shared stories from his four decades of experiences with companies around the world. I’ve broken this discussion into two episodes for you, this one, looking back and reflecting on Jim’s initial vision for lean, where it failed and why, and where he’s seen successes and what we can learn from them.

[00:02:10] In part two, we look ahead into the future. What adjustments do we need to make as a global lean community to achieve greater success with lean thinking and practice? And what advice does Jim have as he passes the torch to the next generation? Before we can understand if something has failed and explore the reasons why for that failure, we need to first identify what the target was.

[00:02:33] And then what actually happened. So that’s where we started. I asked Jim to go back in time to win the machine that changed the world came out. And what did lean being to him then? And what was his vision for what lean’s impact would be today? 35 to 40 years later, get ready to hear some great stories and reflect for yourself upon Jim’s observations in your own experiences of the causes for the gap between his expectation for lean and what’s actually happened today.

[00:03:00] So we can think about what to do differently in the future. Let’s dive in.

[00:03:05] Jim: It’s 1979 was when Dan Jones and I first met at MIT and we were starting the, what became the international motor vehicle program at MIT. And we were looking at an interesting situation in which a bunch of Japanese companies.

[00:03:22] That until shortly before, uh, no one had ever heard of, were steadily taking market from a bunch of American companies and European companies that everybody had heard of and had been familiar with for a long time. So, what to make of this? And we were doing a study that, uh, the first title for the study was Future of the Automobile.

[00:03:42] Which was a sort of big think about the future of automobility. But it rapidly became about something else, which is why, uh, the Japanese were winning and the Americans and the Europeans were losing. And that was not something that we started with, but it’s where the public was. It was where our sponsors were.

[00:04:02] And the sponsors were car companies that, uh, had agreed to participate in this. And some, uh, foundations that were putting money into it and so on. So, uh, there were two theories. Uh, theory A was that the Japanese were winning because they lie, cheat, and steal. Okay. And the deal was that they’ve got secret workers in all of those little second and third tier factories.

[00:04:24] They’ve got a trick currency that’s mysteriously weak. They’ve got strategic targeting by MITI, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry to pick off vulnerable European and American companies. And then they’ve got the Ministry of Finance to sneak them some money. Uh, as national champions. So they’re winning through nefarious practice.

[00:04:46] Okay, that’s theory A. Uh, and theory B, uh, is that they’re actually better at designing things and making things and managing suppliers. And in Japan only, uh, supporting customers, the argument was that a Western companies couldn’t sell anything in Japan, again, because of lying, cheating and stealing. And, uh, we looked at how Japanese distribution worked, which was totally different from the way it worked in the U S and Europe.

[00:05:12] And by the way, it was better, but very expensive and difficult to set up. So is that a trade barrier, or is that good business? Okay, and you can conclude one or the other. So, I said, okay, well, uh, we got Theory 1 and we got Theory 2, Theory A, Theory B. Uh, we should test that. And what that meant, uh, something that academics did not normally do or not much as they’d not do as much as they claimed.

[00:05:37] Let’s go see. So, uh, we weren’t using the term GIMBA, uh, at that point, but we said, let’s go look at these companies. And we went to Europe and we went to the U. S. and we went to Japan. And, uh, Dan and I very quickly said, wow, it’s Theory B. Uh, it’s just in your face. And yet, uh, most Americans and Europeans, uh, managers can’t see it.

[00:06:00] because it’s a complicated system. So therefore, our job is to actually A, produce the evidence of what the performance difference is, and then trace that to different methods. So we started on that in 79. And it took us till 1990 to get the full, complete data together. Well, not just about the factory, though.

[00:06:23] It’s very important. The machine book in 1990 had five, uh, what should we say, substantive chapters. And one was about production. Uh, and the other was about product development. And the other was about supplier management. And the other was about customer support. And the fifth was about management. So that, uh, four fifths of the material in that book, uh, was not about factories.

[00:06:47] But what people were prepared to hear was it’s about factories. And by the way, uh, everybody in the world thinks they know something about factories. Uh, it’s really interesting that you meet people who’ve never been in a factory who tell you even to this day that they know all about factories. Uh, like, you know, Elon Musk says he’s the world’s preeminent authority on manufacturing, which, uh, you know, he knows some things.

[00:07:11] But, you know, come on. This is, uh, no. This is a little bit more complicated than that. Okay. So, uh, people thought that, uh, this was about production. And that was a problem right off. Because we understood that there were five interlocking pieces. And you really got the power of the system from getting all five pieces.

[00:07:33] Interlocked. And so therefore, if it’s just factories you’re going to look at, well, you’re going to miss four fifths of what you ought to be looking at. So that led us down a path. Second thing that happened was that people everywhere love the idea of kaizen. Kaizen. You may hate all Japanese words, but you like that one.

[00:07:54] Yum yum. Let’s have some kaizen. And managers love to pay for some kaizen. And let’s get some fancy consultants in to do some kaizen. A manager doesn’t have to do a thing. Just stand back, uh, open the door. Here come the Shingijitsu guys who had been allied with Ohno back at Toyota. And, uh, in a week, in a week, they will give you amazing payback, make you look like a hero, and that’s what this is about.

[00:08:22] It’s about Kaizen in factories. Okay. Well, if you start off thinking that, well, I would predict you’re going to be disappointed, but. In our work, um, we were aware from right at the beginning that, uh, as in hockey, you’re supposed to hit the puck not to where the player is, but where they’re going to be when they take it and knock it in the goal.

[00:08:43] And so, therefore, we couldn’t hit the puck to a place where no one not only was, but was going to be. That if we started off with this big elaborate five piece puzzle, uh, hardly anybody could do anything with it. So therefore we were happy enough to watch as people went forth to do Kaizen. But we knew it was one piece out of five and we knew the results would be.

[00:09:10] Uh, for the longer term limited, but okay, let’s go. That’s what people want to do. And people did it. It’s just amazing. And, uh, the five day wonder, I went on many of those and just sat in the back and watched the fun. And, uh, the door flies open here. The Japanese consultants, everybody on the floor, get on the floor.

[00:09:28] We’re going to move all your machines. We’re moving your machines. Don’t move. Don’t move. We’re moving your machines. We’re going to reorganize it and process flow. Get out of process village and we get into process sequence and we’re going to take lead time down from forever to four minutes or whatever.

[00:09:46] And it was, it was miraculous. And I watched these things. I was in an aerospace plant, uh, out in California. The day the Shingy guys marched in, and by the way, I never worked with Shingy, that I was just an observer, I asked them, could I just watch you? I wasn’t paid by them. And, uh, the key machine in this airspace plant that built nacelles for engines, and they built them for B 24s and B 29s and B 17s, and now they were building them for Boeing jets, uh, was a stretching machine.

[00:10:15] thing that took a piece of sheet metal and put it over a die and stretched it to give it the current shape. And that machine had been working continuously in that spot for 50 years. 50 years. This is the machine that was installed in 1943 and this is 1993. Okay, and they’re going to move it and it had not, the engineers are just incredulous.

[00:10:39] You can’t move this thing. Nobody can move it. And the shingy guys find some pry bars and start prying the thing up. And it’s massive. And sure enough, within a day, they moved it, okay? And so this was the most amazing thing these manufacturing people had ever seen or ever dreamed of in their lives. You would take the machine in place for 50 years, and you would move it into process sequence.

[00:11:03] And at that time, when I say that time, from 79 on, uh, most assembly operations, uh, the management philosophy had been keep the line running. That’s a very expensive line. And so you keep the line running, and then you have a repair area at the end. To fix whatever problems you might’ve discovered. And that’s the way you do business and a KPI for almost every manufacturing manager and assembly was what was your uptime and a first GM plant I ever went to was in 79, which was the Cadillac plant, uh, Clark Avenue in Detroit in sight of the 14th floor headquarters of General Motors, which is about a mile away, but you could actually see it from the plant.

[00:11:46] And the plant manager told me that he was graded, first and foremost, on 100 percent uptime. And that he was determined to maintain 100 percent uptime. And if he did not, he would get a call at home at 4 in the morning from people down on the 14th floor who were working at night to want to know what had happened.

[00:12:06] That he hadn’t been able to get 100 percent uptime. And in that plant, there were 2, 500 people who were assembling Cadillacs. And in a second plant, which was next door through a door, there were 2, 500 people fixing the mistakes they had made in those Cadillacs, and this was thought to be a good plant. As he said, we really sweat the details, uh, those Japanese plants are building these toy cars.

[00:12:30] We’re building Cadillacs. So that was the view of what good manufacturing was. They thought they were, by the way, that fella said we’re the best. He really meant it. We’re the best. And then you went to parts components plants and everything was in a process village layout. where you had welding and you had painting and you had annealing and you had buffing and you had sandblasting and shot glass and so forth in a different department.

[00:12:56] And every part went from department to department and often in a big batch. Went to central stores where it was stored until it was time for the next step. So the total amount of work was maybe an hour and it would take a month to get through. And so the Japanese guys came in and said, look, let’s do continuous flow.

[00:13:19] And the only way we can do that single piece flow is by getting everything into process sequence. And that means we’re gonna have to right size some machinery and we’re gonna have to line everything up and reorganize everything. And, uh, to a significant extent, that was done across European and American industry over the next 15, 20 years.

[00:13:37] So you go to factories, and I don’t go as much as I used to, but I still go. You don’t see central stores anywhere. Everything is either cellularized or set up in some sort of, uh, assembly type flow operation. Uh, so you could say That we achieved that. Okay. Now, I think that would have happened if there hadn’t ever been any such thing as lean because it had a logical sense to it.

[00:14:02] But nevertheless, you could say that we certainly contributed and to the speed of doing that. It went a lot faster than it might have otherwise. Then, as I go through life, I often go back and look at things. And I go to company A that had done all this cellularization and an assembly line and they had Uh, good performance, and then you come back two years later and everything has gone backwards.

[00:14:27] And you say, well, what happened? Now they’ve got big buffers. They didn’t have any buffers two years earlier. I said, well, we couldn’t really run it. And the problem was we couldn’t get the parts we needed and the parts weren’t good. And, uh, the workforce never really believed in this stuff. I mean, they kind of liked the just pass it on kind of thing.

[00:14:44] Dot, dot, dot. That you would realize there was a disconnect between the management system and the production system we were trying to create. And by the way, you could see the same things in product development and purchasing and so forth said, Whoa, this is not going to be as easy as we thought. So then the next step in the lean world was to say, well, look, let’s get serious about management.

[00:15:08] And one of the serious steps was John Shook’s, um, A3 book, uh, learning, uh, managing to learn, uh, his previous book had been learning to see, which was how you create continuous flow. And it was really an industrial engineering book. By the way, we’ve, uh, at LEI sold a million copies of that thing. Still sells.

[00:15:27] People love it. Uh, they can do it. They can’t sustain it. Okay. It’s, it’s been the, the best book there ever was, uh, teaching you how to do something that you will not be able to do for long. Uh, because there’s a disconnect with, uh, the management system. There’s another thing that we knew from very early on, but, um, became progressively more, uh, urgent, and that was that, uh, most Western companies were doing product development rather than product and process development.

[00:15:57] That actually they would design the product and then they would sort of design a process to make it. But the theory was, well, let’s put it on the floor and people will kind of figure out how to get this thing to work. And the answer was that it took a very long time. Ramp ups were very slow that you often never got it to a very good process, but it was good enough for whatever situation competitively you were in.

[00:16:23] So the idea that, wait a minute, in a company like Toyota, and this will shock you, That Kaizen wasn’t actually that important. And, uh, I learned that actually at a dinner in, uh, Toyota City 1990, uh, when I had been in Japan to launch the machine book and went out to dinner with, uh, one of the senior managing directors of Toyota.

[00:16:46] And he said, gee, I loved your book. It made us look better than we are, but we normally are made to look worse than we are by politicians. So it’s good. We’ll take it said, but look, you’ve completely missed the point that the book is very heavily into urging people to do Kaizen, but for us in the process, development process, we do all of what you call Kaizen.

[00:17:09] That, uh, we do it at the front end. That’s why it may take us a little longer, uh, to get the, uh, design in place. But once we go, we can really go. And what our folks are doing, uh, to correct problems is actually problem solving. You call it Kaizen, but actually you launch a process, it goes like that, whoops, it goes like that, and so then you do Kaizen to get it back up to that, don’t do that, launch a process, it goes like that, and it stays like that because you have a robust design and you have daily management, so I know that in 1990.

[00:17:48] But again, uh, hit the puck to where you know that your teammates can be, not at a place so far down that they can never get there, right? What’s the point of throwing a pass to a football player who just can’t run that fast, even though if he could, you’d score a touchdown. He can’t run that fast. Okay. So we’ve always in the lean movement, been trying to be a little bit ahead of where people are.

[00:18:17] But the consequence of that is that, uh, 45 years, 45 years after Dan and I started thinking about this, how lean is most manufacturing? And the answer is, well, not nearly as lean as it could be, but then wait a minute. We had vast ambition. We wanted to lean government. We wanted to lean healthcare. We wanted to lean retail.

[00:18:39] We wanted to lean logistics. And there it has not surprisingly been a lot harder. So when I use the term failed. Um, what I meant was that we failed to achieve, uh, what I would call Toyota class, lean management, lean production. Hardly anywhere.

[00:18:58] Katie: Across all industries. Yeah. If you were to think back to like, you know, those early 1990s, picture in your mind of what success would have been if you could have, you know, done everything right.

[00:19:08] Jim: Success would have been a dramatic and sustainable, uh, elimination of almost all waste. All right. And a better specification of value for the customer that, uh, one of the things you saw in the Toyota development system was that the chief engineer actually listened to customers and he also listened to the organization.

[00:19:29] So one area, you got the customer, the other area, you got the organization and its capabilities, and he’s trying to reconcile the differences. between what the organization can and wants to do and what the customer actually wants. So it’s not just more value, yes, but more accurately specified value. So this is really what you want, not just sort of what you want as a customer.

[00:19:52] So, we had hoped, uh, that we would, uh, for example, in product development, have a chief engineer system everywhere. It was a real chief engineer, not a faux chief engineer system, but a real chief engineer system. And we would have all the trade off curve analysis that Toyota does, and that we would have the Abaya room that actually worked and did real time, real time problem resolution, and so forth.

[00:20:18] And instead, what you have is lots of Abaya rooms. But you go and sit in the back and listen to the meeting and it’s really, uh, again about excuses and why you didn’t and coming up with good reasons why it didn’t happen. Go to the Toyota Bay a meeting. That’s not what they talk about at all. There’s a lot of proforma lean that we hoped we would be beyond.

[00:20:40] And then there in a number of industries, uh, just got some of the rudiments and then just stopped there. Now let’s go back to the failed word. That sounds like it’s final. Failure is final. I didn’t say that. I said here in 45 years, we have failed to create real lean enterprises. Almost anywhere. I didn’t say we’ve done nothing.

[00:21:03] I said, uh, compared to what I had hoped, I, this is, uh, realized a high mountain, but I wanted to get all the way to the top of that mountain and we have not gotten there. So what’s the countermeasure from where we are right now? And we’ve been working on that, but I will tell you it is, it is difficult that, uh, number one, uh, product and process development.

[00:21:25] Is still mostly product development followed by sort of backfill product development. So we now have a lean product and process development group in our LEI, but that works with a lot of companies and a lot of companies are trying to do real product and process development. Lean. So people are trying, but it’s hard.

[00:21:46] It really is hard. That we’re trying to encourage people to do a better job of bringing their suppliers into the process. Well, guess what? That’s really hard. And an intervening thing that happened between 1979 and recently was that managers said, gee, I could do something hard that might work called lean, or I could do something easy that would work much faster, and that’s called offshoring and outsourcing.

[00:22:16] Okay. Well, I don’t actually have to change any of my behavior. I just get a new set of suppliers on the opposite side of the world and I get some KPIs and we manage them to KPIs and life will be easy and good. So I started writing about that in 2003, did an article for either Planet Lean, I guess for the um, LEI website, but said, before you move to China, do some lean math.

[00:22:42] And what I said was, uh, fix what you got first, because if you fixed it, maybe you don’t need to move. And then if you did need to move, you really ought to calculate the total cost rather than just piece part price plus slow freight, which is what purchasing guys at the direction of the CEO in many companies were doing.

[00:23:01] Wow, we look pretty good on purchase price variance look pretty good on slow freight But that wasn’t the real cost of the company at all There were lots of other costs that just were ignored and just ignored they knew it and they just ignored it. So That’s a big set back to lean That, uh, you don’t have to change anything that you do.

[00:23:22] You can just find somebody else to do it. And now of course we have a political situation, which I wouldn’t say is the inevitable result of that, but is the significant result of that. Now I’ve done another, a more recent thing, although it’s all the way back in 2013, it says before you move back from China, do some lean math, because if you’re going to bring it back and do it in the same crummy way it was done when you sent it off, all we’re going to get is inflation.

[00:23:48] Donald Trump, take note. All you’re going to get is inflation, right? You can absolutely bring stuff back, but can you do it cost effectively? Well, you do the lean stuff. You got a better chance. So that’s, uh, that was a digression for us, a, a diversion, an unfortunate bit of labor arbitrage. That took managers, uh, minds off the real issue, you know, tried to just outsource it.

[00:24:14] So I think there’s no question that slowed down the lean movement that managers thought they had a choice. And I view as that most of that choice was illusory, but there it is.

[00:24:23] Katie: Jim, what are some of the things that you’re, you’ve been seeing over the last two decades of the challenges of getting. Senior managers on board to really like see lean as a better way, you know, I see this as one of the biggest challenges.

[00:24:36] It’s like they’ve been successful in doing things the way they have. What are the things in your work of going to see around the world that have really been some of these barriers of getting more leaders on board?

[00:24:46] Jim: Well, let me tell you what doesn’t work, uh, which again, I thought might work. I would say to senior management, why don’t we take a walk?

[00:24:55] What I call the walk of shame, but I just called, uh, told them it was the Gemba walk. And you go out and you show them all of the waste. Okay, I’ve done this with CEOs, you walk along and by the way, they haven’t got a clue what people are doing, nor maybe should they, but there’s just no mind for starting with the actual work and working backwards, rather than starting with the top and working down.

[00:25:23] So that what, uh, managers would conclude from those walks were, Oh, yeah, we could do better. We should hire some consultants. Oh, yeah, uh, there’s suppliers who say they’re doing better. So why don’t we quit doing it and go to those suppliers? Okay, so that was not what I had, uh, in mind at all. Uh, and then other managers, and by the way, this is, um, a curious thing, uh, really do think they can look at work and immediately tell people how to do it better.

[00:25:51] Because they got some ideas or they heard some buzzwords or they went to a lecture or whatever. And that can be very painful to watch, because the people doing the work know this is nonsense, but they have to sort of pretend to, okay, boss, you know, every problem has the correct level for resolution and how on assembly line six to keep something or other bad from happening is not something for any CEO to think about.

[00:26:17] No, don’t do that. It’s not, not what you do. So things that I thought would, uh, help, I discovered, well, look, I don’t think they hurt, but, uh, they, they didn’t get the result, uh, that I wanted. So what could we do instead? Uh, well, now when I go out with, uh, the CEO, and I still do this, I say, gee, let’s stand here, uh, you tell me about your management system.

[00:26:42] I mean, in the hospital, just a recent example, uh, go to a ward in the hospital with the senior people and say, tell me about your management system. Okay. Well, the management system, by the way, is the charge nurse, the ward nurse. And what she’s trying to do is protect her staff from the organization. Which doesn’t do tech support correctly, which wasn’t get the drugs there on time, which doesn’t have the orders in order, uh, which doesn’t bring the right patient to the right place.

[00:27:12] And so that poor person, by the way, the world’s most miserable job is try to help your people not be destroyed by your organization and you’re standing there and the managers just don’t see it. See, oh, they’re working really hard. Yeah, everybody’s really working hard. They seem very energetic. Well, yeah, or people are gonna die You know, oh my god, I can’t believe this And by the way, in this organization that will be remain, uh, will remain nameless, but they had a, uh, a daily huddle.

[00:27:45] And by the way, those are all over healthcare, everywhere, daily huddle.

[00:27:48] Katie: Came from healthcare.

[00:27:49] Jim: Yeah. And what you see on the huddle board is all the problems. And then you’ve got sort of, uh, what people think is a cause. And then over in the far right column, you have, uh, action. And by the way, you can come back tomorrow, you can come back the next day, you can come back next week.

[00:28:07] But eventually the OPEX people will come around and sum all this stuff up and look for the low hanging fruit and so on. But there’s no real time problem resolution, which is the entire point of daily management. Entire point. So, again, they got the words, excuse me, but not the tune. And, in fact, don’t seem to have much interest in the tune.

[00:28:30] But without the tune, the words don’t really make a good thing happen.

[00:28:34] Katie: I came from health care, which is where I got introduced to lean thinking. Gosh, almost 20 years ago now, I just recall so acutely that challenge of trying to get the real time problem resolution because those charge nurses are maxed out.

[00:28:46] You know, they have like 40 people. It’s like the system doesn’t set up the success on that front line. And as you said, they’re just like doing their best to save people. It’s like, how do we create those systems in the organizations that. allow for that?

[00:28:59] Jim: Well, there’s another thing. If you go and as I’ve done over the years and watch people doing frontline work in healthcare, uh, one of the lean rules, the Toyota rules is that every worker has a coach who is there for the purpose of enabling good work.

[00:29:16] That’s why they’re there to enable good work. Well, that coach has to actually know the work. Okay? Gotta actually know the work, or you can’t help. So here, and by the way, once you get sensitized to it, look, you’ve been in a hospital, you’ve seen it to yourself, but you realize that people are doing things to you that they’ve never actually done.

[00:29:37] Because they got the bag and the parts and whatever. And I say, well, gee, you know, better read this. Cause I’ve never done this or I haven’t done it in a year. Standard work, not so much. Okay. And then when they say, gee, I don’t know. Well, then the charge nurse is busy trying to figure out why the guys from Central Lab have lost the whatever.

[00:29:58] Okay, there’s nobody. You’re on your own. So that’s pretty frightening. But it’s also pretty horrifying. And then if you want to wonder about burnout, well, a good part of the burnout phenomena is simply people being asked over and over to do things that are dangerous, that they don’t actually know for a fact they know how to do, they’ve got to do right now.

[00:30:19] Whoa. You want to work there?

[00:30:21] Katie: No, they don’t have the supplies they need and they’re just trying to do their best. And so

[00:30:27] Jim: that’s why you need this as a system. You need all the parts to go together. You really do need daily management. Uh, you really do need a Kaizen method that works. And again, um, uh, the one week Kaizen was sort of an artificial.

[00:30:41] Uh, kind of thing that, um, they think sometimes was counterproductive, but, uh, you don’t do Kaizen slowly, you try to do it fairly quickly. And yet, uh, you see that many organizations can’t do that. Uh, and then finally you get to the Hoshin part, the strategy part, where the priorities are really not clear.

[00:31:01] And there’s no connection between the priorities set at the top and what people are actually doing at the bottom. And without that, how is this supposed to happen? We’re going to achieve these amazing goals, uh, but nobody at the bottom even understands why we’re doing it and much less how to do it. Not so much.

[00:31:21] We’ve got some work to do.

[00:31:23] Katie: Absolutely have a lot of work to do. I remember too, we were introducing the concept of Andon, which is, you know, fantastic at Toyota. I love going to the Toyota factories and the. The end on the light now is being signaled. I don’t know many times in like even just a 10 15 minute period and that’s important, but it’s the manager or that coaches that that team leader is response to it.

[00:31:45] So you can’t just say, Oh, people tell us when you have a problem. It’s like that nurse example. You say you said we have to have the management system and capabilities to be able to respond to that. Otherwise, it’s also in many ways counterproductive,

[00:31:58] Jim: right? If you can’t respond within the work cycle, um, Uh, you should take your Andon and dump it in the garbage bin.

[00:32:06] Because it just, uh, becomes a, uh, a horribly dispiriting red. And I’ve been in operations, I’m sure you have, that everything’s red. And they say, well, that’s our Andon system. And they say, well, how long has this been read? You know, about a week. You say, well, then throw it away. Because the whole point was, it’s simply a signal that says that an intervention is needed.

[00:32:30] And that has to happen within the work cycle. So, how do we get it so screwed up? But okay, that’s where we are.

[00:32:37] Katie: You’ve gone around the world and we’ve, you’ve seen, you know, some of these challenges. What are some of the successes? I mean, maybe not full transformation, but at least further along the line in what you had hoped would be happening.

[00:32:48] Jim: I try to stay away from company names if I’m going to say anything bad, but I don’t need to say anything bad here. LEI has a few partnerships. It’s a small number with organizations that are trying to do things in most cases that we don’t really know how to do. Because from our standpoint, if we know how to do it, well that’s, hey, fine, some consultants could go do that, but we’re in the business of trying to move the frontier forward.

[00:33:13] So at GE Appliance, which is in Louisville, Kentucky, they’ve got three other facilities, but that’s the biggest. Uh, in 2012, uh, they were trying to reshore. And this is really quite relevant for where we are right this minute, that, uh, the company GE Appliance had been, uh, the American leader in appliances.

[00:33:32] And that was from an early date. I think they got in the appliance business about 1900, uh, by the 1950s, they had built Appliance Park in Louisville, which is one of the largest factories in the world, 25, 000 people, uh, six big buildings. And gosh, they must’ve had 30 million square feet under roof. And they were building massive amounts of appliances, uh, using classic mass production techniques.

[00:33:58] And they had assembly lines. And, uh, by the way, I was there in time to see the old, uh, what it looked like. And there was a parts hospital or a appliance hospital at the end of every line where they were doing rework. And they were trying to hit a hundred percent uptime on the lines, but there weren’t very many lines.

[00:34:17] In fact, when we first went out there, there really were only about two. And so the company had had 25, 000 people and they had outsourced not just production, but product development. Interesting that GE Appliance outsourced appliance design to Samsung and LG in Korea, they created them. Okay. There’s a bright idea.

[00:34:38] So they want to sell the business. Jeff Immelt came and said, we’re not a manufacturing company, really, certainly in terms of consumer products. So they tried to sell it and nobody wanted it. I couldn’t get any money for it because it really was just a marketing and service parts business. And they had 1, 500 people, so they’d gone from 25, 000 to 1, 500.

[00:34:57] So they decided they would recapitalize it, and spend some money, and get their own product development system, and start making things. And then the company would be worth something, and they could sell it. So, in the end of 2012, they called us and said, Well, gee. This manufacturing is kind of hard work because we don’t actually know anything about manufacturing.

[00:35:18] And we’ve got a wonderful product. It was the first for home use heat pump hot water tank, first in the industry, uh, but very expensive, very complicated. And, uh, we’re really struggling, uh, to make this thing. So could you help us? Well, now LEI doesn’t do that sort of Kaizen, but we found some ex Toyota guys, uh, to go out and spend some time with them.

[00:35:40] And over the last, uh, 12 years. Uh, they have figured out how to make things. They have done a tremendous amount of LPPD, that’s Lean Product and Process Development work, tried to rethink their supply base and so forth. And so they’re pretty good. They’ve moved into the number one position in the U. S.

[00:35:58] appliance industry and they have made a lot of money. And I don’t think they could have done that without having finally said, we will do the lean thing. Just for example, one of the issues, big issue when they were still owned by GE was the idea they should have team leaders. That, uh, they had about a 50 to 1 ratio of frontline managers to frontline workers.

[00:36:24] So if you do that, uh, as a worker, you’re on your own. Same as healthcare. And you don’t want to get in trouble, so you just keep moving stuff ahead. And yet it looks great, uh, as the accounting folks back at headquarters look, because you have a very low level of indirect. Somebody just said indirect.

[00:36:43] Anybody who’s not touching the product to add screws or whatever is actually waste. And so let’s get rid of them. You know, Toyota’s always had a five or six to one ratio between, in those kind of operations, between, okay. And so there was a tremendous fight with headquarters about whether they would be allowed to have team leaders.

[00:37:04] Well, okay, then, now get this, uh, it gets more interesting that, uh, they tried to sell it to Electrolux and it was ruled out in Europe on antitrust grounds. And so then they sold it to Haier. And Haier is the Japanese company that makes the little fridges that you have in your hotel room and you have in your dormitory room.

[00:37:22] And they wanted to move up in the appliance world and so they bought GE Appliance. That was in 2016. And, uh, they really didn’t know much about this. So they said to the folks at Appliance, we’ll just do it. And so they left them alone. And they had a spectacular success over the last, uh, eight years. So what is the magic sauce here?

[00:37:48] First off, you have to have some people who actually understand what the problem is that they’ve got. In the GE management, by the time we got there, they said, okay, Everything we used to do is wrong and we got to do things different and we don’t know how to do it. So number one, uh, that we’re doing something wrong.

[00:38:06] Number two, we’ve got to find out how to do it, but then we’re going to do it. This is not going to be some consultant thing. It’s not going to be a program. Uh, we’re going to change our lives with regard to how we manage and how every manager works. Okay, and within product development, we are going to do product and process development.

[00:38:28] We’re really going to do this so that everything we put out is really good, uh, when it hits the floor and we can go to very high output very quickly. Okay, but that takes a lot of work up front. So there’s what I wish had happened, uh, everywhere. And, uh, by the way, there are a couple of people. Who I won’t, uh, they’d be embarrassed if I named them, but there have been a couple of people there that were key players in the organization who said way back when we’re going to do this, and they state that one of the things you see in industry is, uh, you know, what CEOs turn over every three to four years, every CEO has a new program, uh, much of which is just get rid of the old program, you know, Okay, uh, no guys at the top actually understand how you create value at the bottom, but that’s okay.

[00:39:14] They’re going to be gone soon. Uh, just get their program to cycle once and it looks pretty good. And then before you discover it isn’t sustainable, well, they’re off to the next thing and so on. So that’s the world, the reality in terms of where are we going to throw the pass, where we’re going to throw the ball, where we’re going to hit the puck, that they had continuity.

[00:39:33] Uh, what Deming called constancy of purpose, constancy of purpose. This takes years that, uh, the GE guys have been at it for 12 years and they still don’t have everything in place. They’re still working on it. They know what it is. They’ve got an R star. They know what they’re headed for. This is not easy and you can’t do it with strangers.

[00:39:54] Uh, you can’t do it with high turnover. You can’t do it if there’s no respect. Um, and it’s such a simple thing to say that we ought to have respect for people. And Toyota says that. Go see, ask why, show respect. But you have to really mean it. Okay. You have to really say, you know, you’re a good person.

[00:40:14] You’re trying to do good work. My job is to enable good work. Let’s get going. That’s not the way a lot of managers historically have felt. So we’re still working on that. If you ask me now, by the way, I’m, uh, you know, don’t. Don’t ask how close I am to the end of the runway, but, uh, you know, every time you get on the airplane, you look out in the States, they have those numbers on the runway, which is thousands of feet left.

[00:40:37] And by the time you get down to about three, well, you really ought to start to feel the nose going up. And certainly by the time you get to, I’ll be getting off the ground. Well, I’m down to about one. Okay. So I haven’t got a whole lot of runway left. So on my watch. Uh, you know, come on, uh, not that much more is going to happen, but what I’m doing right now is just trying to reflect a little bit on where we’ve been and where we need to go.

[00:41:04] Again, clarity of North Star. So if you don’t know what your North Star is and you don’t have constancy of purpose, I can predict, uh, with pretty great confidence that you’re not going to accomplish much. If you do know what your North Star is and you have constancy of purpose, but you don’t have the fundamental knowledge to be effective as a lean leader or a lean follower or lean anything else, well, I can fairly confidently predict you’re not going to have much success.

[00:41:33] Okay. So it’s a combination of intent and knowledge. And we’ve really worked hard to fill the knowledge in, by the way, this is really important that Mark Reich has got his book together on Hoshin that’ll be launched at the LAI Spring Summit in March in Atlanta. And the gentleman at Toyota, Japanese gentleman, who actually was present at the creation of Hoshin planning.

[00:42:01] Way back in the 60s is actually going to give a talk. Wow.

[00:42:04] Katie: I’m

[00:42:04] Jim: excited. I’ll be there. It’s okay. Be there. Uh, really interesting. You know, the host in peace is just hard. We tried doing it my first year of running LEI and honestly, we just nearly killed each other. The great thing was deselection. Just everybody was dug in on their piece of the puzzle was the most important, and we need to fix that first.

[00:42:25] And I called in an outside moderator, you know, with brought control rods to keep the reactor from melting down, and it still didn’t work. So, hang on, there’s a lot of this lean stuff. That A, it is a practice, and B, it has to be a practiced practice. So you try it and you have to have some tolerance for failure.

[00:42:45] Uh, on Hoshin, you try it the first year. I never heard of a company that could do Hoshin very well at all in the first year. And Mark’s been at this for years. He was at Toyota for 23 years. His job was to actually install Hoshin in North America for all the Toyota operations. And Mark can tell you it takes five years before you can really get it to be smoothly incorporated into a complete system.

[00:43:12] which is, don’t forget, daily management plus Kaizen, uh, with A3 plus, which also has A3. So it takes years of practice. How many of us have the patience for years of practice? Because we’re not going to be

[00:43:26] Katie: there anyway. Exactly. I mean, that’s what happened in one of the healthcare organizations. Like the leader knew we needed, it was going to take five to 10 years.

[00:43:33] And, you know, you start with that top level. And I remember, as you said, like, just putting all the initiatives up there. Everyone’s eyes were like, wow, we have to like, how could we, there’s no way we could do all of this, but the deselection took several years. And of course, then we had a change in leadership and things shifted, but knowing to get all the way down, it’s going to have that catch ball in that conversation.

[00:43:52] It’s, it’s a long term play. So how do we get out of this short term

[00:43:56] Jim: approach? So I always tell people that the managers at Toyota have all been there all their lives. Uh, this is absolutely not a program. And that, uh, many of the hosting they take on are three to five year projects. Okay, this is not, uh, not simple stuff.

[00:44:15] If you don’t have continuity, and you don’t have clarity, well, you’re probably going to wind up where we’ve wound up. Okay? So, look, uh, just to sum up on what did Lean do, uh, we did a lot. Uh, that we got people out of process villages into a process sequence. We got people beyond the notion that you should have a low level of indirect to direct.

[00:44:40] We got people in product development to understand you really need a chief engineer for every product, and they have to be there for the life of the product. Okay, you can’t change them out every year. We’ve convinced a lot of people of a lot of things. But, wait a minute, we took a detour, uh, with, uh, offshoring, outsourcing.

[00:44:59] Which we’re now going to come back from, maybe, and maybe successfully, and maybe not successfully. We’ve got a long ways to go. Let me just give the example, which Dan and I were aware of by 1980. That Toyota had a group of suppliers, 300 in the Toyota group, and there had been no change in those suppliers since the war.

[00:45:19] By the way, there’s been no change in that supplier group since then. Okay? These 300 companies have all been together for 60 years. Now there’ve been some new added because they, to go abroad, they just couldn’t, uh, scale up. So they’ve added a lot of, uh, Uh, strangers, but they bring them on, it takes quite a while.

[00:45:37] Katie: And they train them and they develop them. Like even down in Kyushu.

[00:45:42] Jim: And then they do value stream analysis. And by the way, that’s where you do it is in process development. There’s the plan for every part. What’s more than that? You’re looking from raw material to the customer at the flow of value and every step is being evaluated.

[00:46:01] Does that create value or it doesn’t? Are we doing it in the best way? It does create value, so let’s continue. But are we doing it in the most valuable way? And that’s where you can do a target costing, uh, rather than taking bids. You know, Atari doesn’t take bids on prices. They say, look, uh, this steering wheel to the customer’s worth 12.

[00:46:22] How are you going to make it for 10? So you have a good margin and we can get sell it to the customer. And we have a good margin. How are we going to do this? It isn’t magic. And it isn’t, we’re just going to beat you around the head. Let’s together go take a walk and look at the entire process and do a value stream analysis.

[00:46:40] And see what we come out with. So they’ve been doing that with many of these companies for 60 to 70 years. And then, Toyota guys strictly hire from the bottom. That they did some lateral hires in the early years, and that was really tough. But now everybody in North America who works at Toyota has been there their entire career.

[00:46:59] Is that good or bad? But what it is, is cycles of learning. Cycles of A3. Cycles of problem solving. Okay, that’s how you train people. By the way, they don’t send people to business schools. They don’t recruit at business schools. Sorry about that. To all the business school folks who might watch, uh, what you do.

[00:47:17] But they don’t. And instead they take people at 18 or 22 and say, Hey, look, we’ve got a 30 year plan for you. And I just met a young woman, um, recently in the States, not long ago at all, uh, in Georgetown, uh, who was about seven years in and a very, very competent person. And I said, you had some choices when you got out of college of where to go to work.

[00:47:42] Uh, why did you go to Toyota? And she’s an immigrant, um, actually from Iran, family had come from Iran and I think she was probably born in the States, but anyway, said, well, everybody else wanted to talk about the benefit package and all of, you know, the stock offering or whatever. And Toyota said, we’ve got a 30 year plan for you.

[00:48:02] Here’s the 30 year plan. I’m seven years in. And by the way, they’ve come through. They taught me what they said they were going to teach me. And by the way, this is very challenging work. It’s very hard here, but they’ve been good to me. I’ve been good to them. I think we got a deal here. And I thought, whoa, why doesn’t everybody work in a situation where there’s a plan?

[00:48:25] And by the way, plans, uh, you know, everybody talks about planning’s invaluable, but the actual plan just has to be modified because reality gets vote. But, uh, why doesn’t everybody, uh, work in an organization where there’s a plan, where you’re continuously learning things? And where you’re continuously able to take on higher and higher level challenges.

[00:48:46] Now, the final thing about Toyota, and we’ll see whether they can sustain it, that they have always carried a lot of extra cash. Because, uh, they said, we want our suppliers never to have to have the brunt of our mistakes. And we don’t want our employees to suffer either from management’s mistakes or mean things that happen in the world.

[00:49:05] And the only way we can buffer that is with money. And everybody who’s ever looked at Toyota’s finances over the years says the company just, uh, grossly underleverages its money, okay? And every B School professor said, you know, well, wait a minute. They’ve been for the last, uh, 75 years, they’ve never had to lay off a permanent employee.

[00:49:27] Because they had the money to sail through, uh, the troughs. And other companies just never even thought about wanting to do that. Much less doing it. Now, by the way, this is the toughest thing they’ve ever seen, what’s going on right now. That, uh, this is just all, all crazy stuff. Right? You’ve got tariffs.

[00:49:47] You’ve got, uh, volatile markets. You’ve got crazy new technology that Nobody really knows what the right bet place is. So they got a portfolio of technologies They’ve been backing at great expense and so far they’ve been able to do it I can’t guarantee they’ll see it all the way through but wait a second They’re just really in a class of their own on that everybody else Trying to leverage trying to cut it as close as they can People by the way are costs.

[00:50:16] They’re not assets Okay, whatever most companies say, actually, the employees are cost, they’re not access. So do you have respect or you don’t have respect?

[00:50:25] Katie: We have it backwards. We got it backwards. What do you think? Has lean failed or rather has the lean movement failed? We haven’t achieved Toyota class lean systems that exist across all industries and around the world.

[00:50:39] And we haven’t seen Jim’s ambitious goals for dramatic and sustainable elimination of almost all waste and a better specification of value for customers in all industries. Yet lean thinking and practice has influenced the world and made industry and services better for people and process. Lean principles continue to be relevant for today, and lean has great potential if we can make adjustments based on what we learned over the last four decades.

[00:51:05] So let’s use our problem solving skills based on the plan do study adjust cycle, or plan do check act cycle, and reflect and adjust on our approach. As we end this episode, reflect on Jim’s observations about some of the Lean movement’s failure points, including how much of the world sees Lean only as about production and manufacturing, and not about management systems, product and process development, or supplier relationships.

[00:51:30] Kaizen is seen as isolated events outsourced to consultants rather than part of a continuous system wide improvement process and leadership mindset integrated into daily management. There’s a lot of leadership turnover and outsourcing of leading lean to internal and external consultants. We have short term focus and offshoring that’s negatively impacted company’s commitment to people and learning.

[00:51:54] And many companies don’t have a really clear strategy or Hoshin that’s connected from purpose at the top, all the way down to the front line. Reflect to on your own experiences. If you’re a lean practitioner, a leader, what have been some of the causes for lean, not working as well as you’d hoped in your organization?

[00:52:11] And what are some of the elements that have contributed to success? As we look into the future, what can we do as a lean community to change course, to make adjustments, and to keep our aim on Jim’s vision for broader and deeper adoption of a full lean enterprise? You won’t want to miss part two of my conversation with James Womack, where we dive into these questions and Jim’s advice and the reflections about lean’s relevance into the future.

So be sure to subscribe or follow Chain of Learning on your favorite podcast player or YouTube so you don’t miss the next episode or any episode. Thanks for being a link in my chain of learning today. I’ll see you next time. Have a great day.

Subscribe to Chain of Learning

Be sure to subscribe or follow Chain of Learning on your favorite podcast player so you don’t miss an episode. And share this podcast with your friends and colleagues so we can all strengthen our Chain of Learning® – together.

About James (Jim) Womack

About James (Jim) Womack