What Lean Was Meant to Be vs. What It Became

What have we really learned after four decades of lean?

Is lean thinking still relevant today?

And importantly — what needs to change to ensure its future success?

In the previous episode, I sat down with James Womack, founder of the Lean Enterprise Institute, to look back on 40 years of lean thinking and management since the publication of The Machine That Changed the World.

In this episode, we look ahead to the future of lean and dig into big questions, including those submitted by listeners:

- Is there a better term than “lean”?

- What would Jim do differently if he could reintroduce lean to the world?

- How do AI and new technologies fit with the application of lean principles?

- What’s Jim’s greatest surprise over the past 45 years?

Jim doesn’t hold back in this discussion — and provides his advice as he passes the baton to the next generation of lean leaders.

In this episode you’ll learn:

✅ Why lean principles still apply even as technology evolves and takes over tasks once done by people

✅ What’s stopping organizations from fully embracing lean principles and practices

✅ Why lean must be leader-led—not outsourced to consultants or internal operational excellence teams

✅ How developing people’s capabilities for problem-solving at all levels is critical to success

✅ The true role and purpose of management

Listen Now to Chain of Learning!

If you are passionate about the potential of lean’s impact now and in the future, this is an episode you won’t want to miss.

Watch the Episode

Watch the full conversation between me and James Womack on YouTube.

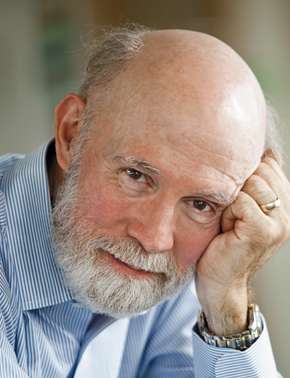

About James (Jim) Womack

About James (Jim) Womack

James P. Womack, PhD, is the former research director of MIT’s International Motor Vehicle Program who led the team that coined the term “lean production” to describe the Toyota Production System. Along with Daniel Jones, he co-authored “The Machine That Changed the World”, “Lean Thinking”, and “Lean Solutions”.

I recommend “The Machine That Changed the World” among my 10 top books on Lean Management and Lean Production.

James is the founder of Lean Enterprise Institute where he continues to serve as a senior advisor.

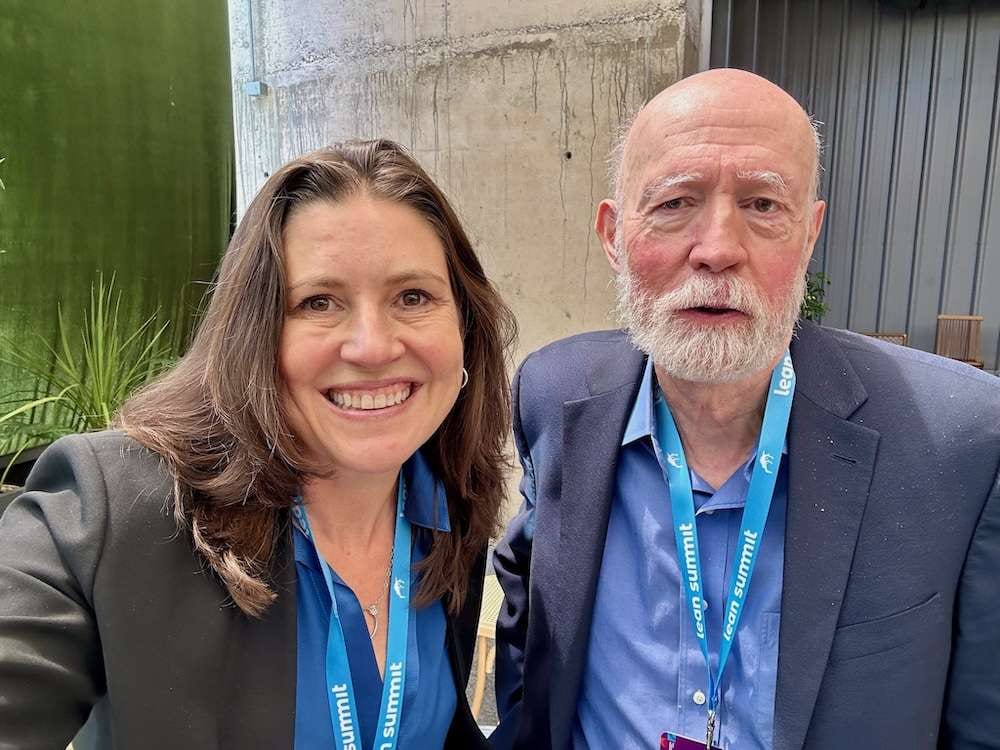

I first met James (or “Jim” as I call him) nearly 15 years ago when we were both speaking at a lean conference in Australia. Since then, our paths have crossed many times, most recently in Santiago, Chile, where we spent time digging into the history and future of lean.

He has also endorsed my book Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn:

“Katie explains how Yoshino found his North Star, overcame adversity, framed situations in a positive way, learned from failure, and always developed the people he worked with as well as himself. If you reflect on and heed its wisdom, you will become a better person, and a better coach and manager. A gift to treasure in a dark time.” — James P. Womack

Reflect and Take Action

One of Jim Womack’s biggest insights?

Lean can’t be outsourced.

Too many organizations delegate lean to consultants—internal or external—or treat Kaizen as a one-off event. But real, lasting transformation happens when lean is a practiced practice, embedded in daily leadership and embraced at every level.

As we look ahead, let’s take up James’ challenge and focus on what it really takes to sustain lean transformation:

✅ Assess your leadership approach – Are you coaching and developing problem-solvers, or are you taking on all the problem-solving yourself?

✅ Embed Kaizen into daily management – Move beyond Kaizen as an event. Make it part of a connected system that continuously improves.

✅ Practice lean at all levels – Have a constancy of purpose and seek ways to innovate that allow managers and leaders to be coaches.

What’s one thing you’ll do differently to ensure lean is truly leader-led in your organization?

Important Links

- Connect with James Womack

- Check out my website for resources and working together

- Follow me on LinkedIn

- Learn about my Japan Study Trip program

- Listen to Part 1 where lean has failed and succeeded: Episode 37 | Lean Has Failed (or Has It?) with James Womack

- Hear about the impact of my Japan Study Trip leadership program from past podcast guests including:

- Episode 32 | When Crisis Strikes, Hold on to Your Purpose with Isaac Mitchell

- Episode 12 | Beyond Appearances: Building Real Continuous Improvement with Patrick Adams

- Episode 30 | Fostering Excellence Through Joy and Respect for People with Stephanie Bursek

- Episode 20 | How to Coach Executives and Influence Change with Brad Toussaint

- Listen to highlights from the GE Lean Mindset Event where we talked about the power of lean on Mark Graban’s podcast: Discussing the GE Lean Mindset Event with Jim Womack, Katie Anderson, and Jamie V. Parker

- Read the accompanying blog highlighting the event: Highlights from GE’s “The Lean Mindset”

Listen and Subscribe Now to Chain of Learning

Listen now on your favorite podcast players such as Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Audible. You can also listen to the audio of this episode on YouTube.

Timestamps:

01:48 – Two things Jim would do differently in introducing lean

03:92 – Why consultant-driven Kaizen falls short

05:29 – The origin of the word “lean”

08:29 – The alternative label instead of the term “lean”

10:26 – How lean intersects with emerging and established technologies

14:43 – Analyzing AI’s effectiveness through the value stream

16:02 – Jim’s greatest surprise of the 40 + years of lean

19:10 – Changes at Toyota’s Operations Management Development Division

22:27 – Why problem-solving skills matter at every level

23:34 – Jim’s parting advice for the next generation of lean leaders

Full Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] James: If every worker is actually a problem solver, if every manager can enable people to do problem solving, well then, uh, you’ve got a lot of time left over to do true improvement.

[00:00:13] Katie: Welcome to Chain of Learning, where the links of leadership and learning unite. This is your connection for actionable strategies and practices to empower you to build a people centered learning culture, get results, and expand your impact so that you and your team can leave a lasting legacy.

[00:00:28] I’m your host and fellow learning enthusiast. Katie Anderson. Is Lean relevant today in the 21st century? What can we learn about how Lean’s been applied over the last four decades, and how we can adjust our approach for greater success of adoption globally over traditional management? In the previous episode of Chain of Learning, James Womack, the founder of the Lean Enterprise Institute, an MIT researcher whose book, Machine That Changed the World, launched the Lean Movement globally four decades ago.

[00:00:58] And I reflected on how Lean’s failed and where it succeeded in achieving his ambitious visions for global lean transformations over the last 40 years. If you haven’t listened yet, hit pause now and go back to episode 37. In this episode, part two of my conversation with Jim Womack, we pick up our conversation about how to adjust and move forward into the future for greater success.

[00:01:20] We explore what Jim would change about how he introduced Lean to the world, including what he thinks about the choice of the term Lean itself. How technologies such as AI and Lean can integrate, and his parting words of advice for us as he passes the torch to the next generation of Lean and continuous improvement leaders.

[00:01:38] Let’s start with my question to Jim. If there’s one thing he could go back and change about how Lean was introduced in the world, what would it be? Let’s dive back in.

[00:01:48] James: Well, there are two things I would have gotten going earlier on the product development piece. It’s just really hard to do a good job of making a product, uh, using a process that’s just wrong.

[00:01:59] And we did the best we could. By the way, um, I’m deeply indebted, we all should be, to Jim Morgan and Jeff Leiker, who, uh, were the first to actually explain in terms you could understand how the Toyota development system works. Uh, but we didn’t have that for many years and so therefore we were just accepting as a given these lousy processes that were out there and more being added all the time and furiously trying to fix them.

[00:02:27] So that’s one thing I wish we’d been able to get going on that and I wish we had been able to describe the complete management system in actionable detail. Because, uh, TPS was written down by 1967. By the way, Toyota only introduced the term TPS when they needed to bring their 300 suppliers up to the Toyota level.

[00:02:51] And that was in 67 after they launched the Corolla and realized they had the world, uh, to conquer. They could do it. And so quickly they had to get suppliers to go. And so the TPS house was invented at that point. And they actually called it TPS, which had never been not language used inside Toyota. The system was much more teachable and it created a sort of false notion that if you could just get the factory, right, you could get everything right.

[00:03:21] And that really wasn’t true. And then the third thing, if I could change something would have been to say earlier. that, uh, this whole notion of consultant driven Kaizen just can’t produce the results that you’re looking for. Okay. And I kind of knew that, but I was, look, we we’ve, uh, LEI never thought of ourselves as being the consulting business.

[00:03:43] I’ve never been a Kaizen consultant. But I needed those people to, uh, energize people to try things I needed for the conference. We were running. Uh, every consultant would call me before the conference and say, I want to make the lean speech at your conference. And I say, none of you will ever make the lean speech at our conference.

[00:04:03] Send me your best student, your best company. And let me see if I can get the CEO to make the speech. So I needed the consultants, but I realized that this, you know, kind of bill by the day stuff and, uh, mostly was solving specific problems rather than teaching in a sustainable way, a system. I knew that wasn’t going to produce the best result, but that was the best I could do at the time.

[00:04:29] So, if I could have gotten started earlier on the three things I just listed, uh, hey, maybe it would have been a better world, but wait a minute, uh, this is all hindsight. It’s all obvious, doggone it, it was so obvious, but at the time, I was doing what I could.

[00:04:45] Katie: Yeah, and we may, I mean, there’s such great progress, and if you hadn’t done those things, it may not have happened at all, so, you know, I think it’s seeing things as not, as you said earlier.

[00:04:56] Not a complete failure, but maybe failure for the full vision, but looking at where we’re going. I, I don’t, someone asked me a question also related to if you would do something different. I was around the term lean, and I remember when we were together at the lean summit in, I think, Nashville in 2018, and we were both giving talks.

[00:05:14] I loved the talk, the history talk you gave about the origin of how you and your team came up with the word lean, and Fragile being one of the other terms, but if you could go back and, you know, I guess would you change the name? And if so, what do you think is a better term to get people more, um, I guess, deeper understanding of what this is really all about?

[00:05:35] James: Yeah, we thought about it that the thing we liked about lean was it was a short, simple word that Americans, um, you know, you have a word association thing. Lean sounds pretty good unless you think it also means mean. But hey, maybe it means green. It wasn’t a bad word. It was short. It could be, uh, incorporated into other languages as a neologism, uh, because if you didn’t have an equivalent, we’ll just slip four letters into your language.

[00:06:04] You can say it even if you’re French and say lean. So therefore there’s something to be said by something that’s short and memorable. Emphasize that you could create more value by removing waste, and that was the whole point of lean. I don’t know when the term lean and mean came into common use. I don’t, I really don’t know whether that was before or after 1987.

[00:06:30] But, uh, you know, that of course causes us to grind our teeth. Many things cause us to grind our teeth. That’s too bad that we got to lean and mean. So, when we were in 87, we had the evidence, finally, that John Krafchick, wonderful young guy, now, um, gosh, John’s 63. It’s amazing. It’s amazing. We needed a name for this thing, and John had written an article for the Sloan Management Review at the Sloan School at MIT, and it said the triumph of the blank production system.

[00:07:02] And it was blank. And, uh, we’ve been working on this for quite a while. We had all the charts and all the analysis and the regressions and all this stuff done, and it was good to go, but we didn’t have a name. Because we hadn’t had a name, we just sort of called it the Toyota thing or something. So I got everybody in the room, still remember the whiteboard, it’s in the second floor of building E40 at MIT, just a block in from the river, Charles River, and said we’re not leaving this room until we’ve got a name for this thing because the MIT Sloan Review has to go to press, I don’t know, tomorrow or something.

[00:07:35] So we’ve been talking and talking and talking, we’re gonna, what are we gonna do? So I said, uh, let’s name it. Here’s a hint. Let’s name it for what it does. So I said, hey, what does it do? And the answer was, well, it takes less human effort to produce a given product. And it takes less time and less space and less inventory and fewer defects.

[00:07:59] And so I said, less, less, less. And then John, uh, I hadn’t had the term lean in mind at all. John said, let’s call it lean. I can remember the second, and I went to the whiteboard and wrote Lee, looked at it, but wait a second, other people in the room, uh, led by John Paul McDuffie, who’s been at, uh, Wharton School at Penn for years, wonderful guy, and Hiro Shimada from KU University, uh, immediately, uh, have an alternative, which is Fragile.

[00:08:25] And they said, we should call it fragile to emphasize that this is not just a technical system, but a socio technical system, unless there’s human engagement, it cannot be sustained. This is not just industrial engineering. So Dan Jones was there. I was there. John Krafchick was there. We just looked at each other in horror and said, wait a minute, we’re going to go out and talk to CEOs in lots of industries.

[00:08:50] We wanted to, then we said, Hey, this works for anybody. So I’m going to go to a healthcare CEO or an aerospace CEO or a retailing CEO and say, I want you to embrace fragile production with fragile management. Tell me how long that conversation is going to last. No. So. Uh, you know, I think, uh, John Paul and Harold said, yeah, well, you know, I guess you’re going to do what you’re going to do anyway, but we didn’t want to say that.

[00:09:18] So we said, okay, you’ve now said that now, by the way, uh, what they were saying was absolutely true. We knew at the time it was true.

[00:09:24] Katie: Yeah. Who wants fragile?

[00:09:27] James: So there we were with lean. Um, honestly, I don’t think it would make any difference. Uh, the word doesn’t sort of mean anything now. It’s just that Toyota stuff.

[00:09:37] So you could have called it Smucko. And now instead of Smucko, a word that people have been using, but no one’s lost track of what the heck it means, it’s just that Toyota stuff. So I think we would have wound up in the same place. I don’t think that just, uh, changing the label, uh, changes the reality.

[00:09:56] Katie: And people’s association with that word, right?

[00:09:58] So it’s That’s how things started versus seeing the totality that you even painted the picture of with all those five areas back in, you know, 1990. I have a few other questions that a few people asked and I thought would be interesting as we’re thinking about how do we course correct and move forward into the future?

[00:10:14] And one is around How to integrate lean thinking and practice with continued emerging technologies like AI and, and much more. I mean, we’ve, it’s always been there as technologies advanced, but how do you see this intersection with lean thinking practice with emerging and established technologies?

[00:10:32] James: Well, nothing is going to change, uh, about one simple feature of the world.

[00:10:37] That, uh, value, all value is created through a process. Okay? And, uh, look, uh, maybe you’re, uh, selling pet rocks. What are pet rocks? Probably nobody listening does. But a pet rock is just a rock. And you call it a pet rock, and that’s it. You’ve manufactured a paperweight, basically, with a face on it. Well, you only need one person to both design and make a pet rock.

[00:11:01] Okay, or a paperweight. Well, you know, here’s a rock. It’s a paperweight. You just said that. You put it on some paper. You got a paperweight. So, there might be a few products in the world that are not the result of a value creating process. But for most products, you’re going to have a development process and a fulfillment process, and maybe a customer support process, and that doesn’t change.

[00:11:26] So then there’s work to be done, and our definition of work is simply those actions that create value. And those actions that don’t create value might be incidental work, that they’re necessary to do the value creating work, or they’re waste. So now, we’ve got an activity, and right now it’s being done by humans, and you say, well wait a minute, this could be done by a robot.

[00:11:50] Or let’s suppose it’s an office activity. It could be done by a GPT. So that step that a person was actually doing, you don’t need to do anymore. So out goes the person, in goes the GPT. So there are a couple of questions. Uh, what happens to that person? Um, you know, you throw them out the window, uh, or, you know, drop them off the, the, balustrade at the top of the building.

[00:12:15] Surely not, but that’s the way a lot of employers act. Wait a minute. It’s really easy to replace a human with a GPT or a robot that may not at this point be all that capable. Okay, so now what do you do about the fact that the robot’s not actually all that capable? And that’s the deal with full self drive at Toyota, at Tesla.

[00:12:40] Okay, the fact is right now full self drive is better than the average driver. Full self drive still makes a lot of mistakes. So here we are at the truck company and we say, hey, let’s get rid of our drivers. Except, wait a minute, uh, full self drive is still not quite perfect. So what’s our stance on that?

[00:12:59] And the answer is, well, we have a coach. Somebody who’s watching. Somebody who’s making sure, and that could be a co pilot, but it also could be somebody in a control center. But, I find it hard to believe that we just very, very quickly substitute people completely. Uh, for automated processes. Uh, here’s a nice example that it was a recently, um, in the media.

[00:13:23] A study that had been done in which you had some fancy Harvard professors trying to make difficult diagnoses and they matched them up against whatever Dr. Watson or Dr. AI or whoever. And it turned out that the AI got the diagnosis right 90 percent of the time. And the doctors, these were very good doctors, got it right 80 percent of the time.

[00:13:44] These were the tough diagnoses. So of course, all of the attention in these articles is the fact that the, that AI is 10 percent better than doctor. But wait a minute, AI is only 90 percent correct. And not only that, we don’t know how the AI figured out the wrong diagnosis. Okay, so we’re going to say, well look, 90 percent is good enough, get over it and move on.

[00:14:10] Or then you’re going to create a whole new industry of people who try to figure out what went wrong with the AI. And my guess is it’s going to be that because, uh, actually when a machine is killing you, uh, no, I think casualty rate is acceptable when your doctor’s killing you. Well, it turns out that this is tough stuff, and there’s some subjective and this and that, but the funny thing is people are not going to apply the same standard to the human doing the work as they are to the robot doing the work.

[00:14:42] So, don’t forget the analytic deal here is let’s look at the value stream. At each step, let’s say, what’s the best way to do this? And maybe at that step, something that’s totally automated. Okay, well, we’ve got to take care of the people that otherwise are going to be dropped off the roof. Show respect.

[00:15:01] We’ve got to do the right thing. But the other thing is that the game’s not over. Because, as I said at a point on a different topic a little while ago, everybody needs a coach. Well, guess what? AI needs a coach as well. So therefore, uh, this is not, uh, simple, but this is not going to change things, uh, quite the way and quite the rate that we think.

[00:15:25] You can still, if you, if you want to do value stream analysis, you can always find a way to do something better. And there are lots of ways to do it better, and so it’s an ongoing process. But we’re not irrelevant.

[00:15:38] Katie: No. And, and it’s about going back to the principles, right, and letting that drive us and shape how it evolves.

[00:15:44] The, the situation might be changing, the, the inputs might be changing, but how do we apply the principles to keep, you know, respect for people and continuous improvement and all of that happening as well. Two more questions for you, Jim. One is, what is your greatest surprise of this 40, 45 year period?

[00:16:02] James: Well, my greatest surprise was that people could confuse. Doing something for creating value that, uh, we’re going to do some Kaizen here and Kaizen’s good and we’re good people. And so therefore we’re going to produce a valuable result. And so you produce a good result. Which, from my knowledge base, I know for a fact is not sustainable.

[00:16:26] The minute you shut off the Clege lights and you get all the observers out of there, and the consultant goes away, and yet this, uh, sort of childlike faith in the fact that you did the right thing, you did this almost sacred thing called Kaizen, and so you’ve now done your work. Let’s move on. Good grief.

[00:16:47] Can you believe that? Remember the first time I saw a Kaizen newspaper, which was a favorite thing of the Japanese consultants. You get to the end of the Kaizen and there are all these things written up there. And then I would raise my hand and say, well, who’s going to do those things and when are they going to do them?

[00:17:02] So, oh, well, you know, quality is going to do this and industrial engineering is going to do this and say, well, when, when, and then you come back a month later and that a piece of paper with those listed items is still there. And nobody’s done anything. Okay. Because they’re busy. They said, well, you know, we got busy.

[00:17:19] So just amazement that people would believe. That just doing something with no plan for how you sustain it would produce a sustainable result. By the way, let me just say one thing that’s connected to that. Uh, something again. When I first started seeing organizations putting together operational excellence teams, I said, Whoa, now wait a minute.

[00:17:42] Um, operational excellence, the way they’re planning to do it says that the line manager doesn’t actually have to do anything. Other than call OPEX, okay? They can delegate the problem. And so some people who don’t work there, who’ve got lots of other things they’re supposed to be doing, why would we think that they’re actually going to be able to sustain, uh, correct and sustain whatever it is they’re working on?

[00:18:10] And so that’s another, uh, thing, uh, to me that’s been surprising, is how much faith people place in an institutional solution that in my view can’t solve. Wait a minute, what should OPEX be doing? Well, at Toyota, and this is very interesting, the Operations Management Consulting Division at Toyota was set up by Taiichi Ohno in 1967 for the purpose of bringing all the suppliers up to the Toyota level of performance.

[00:18:39] And they did TPS to the suppliers. Door flies open, walk in, everybody get back, we’re moving machines, no talking, no ask questions, here’s what we’re going to do, do this. Okay. And they were in a desperate situation and they actually could get it to go. But, even from that point, they were working on sustainability because the management system at Toyota was quite different.

[00:19:06] And then, about 10, I don’t, I need to look up the date, but it’s maybe been 15 years, but they changed the name at Toyota from the Operations Management Consulting Division to the Operations Management Development Division, O M D D. And now if you go talk to that group and you say, what do you do? And they say we build the capability and managers to solve their problems.

[00:19:30] That’s what we do. By the way, they still have, um, these crazy, uh, jishiken things that they do in one, one a year in most plants, which is just a move the goalpost. Let’s do something really crazy. And by the way, these OMDD people are very smart process people, and they may be aware of some things that, uh, the line managers haven’t heard about, about what might be done.

[00:19:53] But nevertheless, uh, they completely changed what OMDD does. And yet most OPEX programs are still running around solving problems. Okay. So everybody stand back. We’re going to solve the problem. We solved the problem. See you later. Okay. Well, that feels good. And the man, the land managers love it because now it’s somebody else’s problem, but it’s not the way to, uh, to win.

[00:20:17] Katie: No, you described just then my, my journey too, when I first got introduced, I was one of those OPEX process improvement managers go in and solve the problems and it’s exciting leading those events and doing all that work. And I learned over years, like things weren’t sustaining yet. We had that laundry list that, you know, that newsletter of things not take action.

[00:20:37] So we had all this energy and enthusiasm and made some improvements, but it wasn’t sticking. It was through that process that I saw that my role in our team’s role had to shift from being the doers to the teachers, the developers, the trainers with some, you know, doing to help show how to do it, but really shifting that mindset.

[00:20:53] And that’s sort of my passion is helping, helping OpEx people. Like those of you who are listening, we have to move from being the doer to the coaches and the developers. Otherwise it’s not this vision of our change is not going to stick.

[00:21:05] James: Well, look, another thing though, that’s just part of that was the Toyota thought that every, every worker.

[00:21:10] Every line worker could be sought a simple eight step problem solving method. And when something goes wrong and there is the time, they say, well, gee, what do you think’s going on here? Why do you, and that’s when the team leader says, what do you think the problem is? Well, okay, well, we haven’t got time to dig into it, but let’s get back to that.

[00:21:26] Because the team leader in a Toyota facility actually has a lot of time. Because, uh, think about this. I was in the, the, just before the pandemic down in Kyushu at the, uh, Lexus mother plant, and they’ve got three lines and I’ve spent a good bit of time with one of the lines. And they’ve got a thousand people working on the line.

[00:21:45] They’re producing a car a minute. And yet there are 1100 and Paul pulls and on pulls a shift. Well, but think about it for a minute. Uh, each team leader had four or five workers and that meant that team leader had to deal with four or five issues that came up during eight hours. Well, wait a minute, and this was a very quick problem resolution process.

[00:22:07] So mostly they’ve got time to think about, A, what was the root cause of that thing that just happened? But also, how could we improve this? You know, and they’ve got an improvement activity they’re always working on. So, if every worker is actually a problem solver, if every manager can enable people to do problem solving.

[00:22:27] Well, then, uh, you’ve got a lot of time left over to do true improvement. In our world, uh, most workers are not expected to have anything other than just what’s your hunch. You know, just what, what do you think is going on here? There’s no method. And most line managers delegate problems. And then you’ve got a bunch of OPEX people who, whatever, uh, nobody’s learning what they need to be learning.

[00:22:52] So if you think that, uh, the key thing. What’s going on is that everybody is being developed, that everybody at every level is improving their skill level. Not in terms of just the work itself, but in terms of how to think about the work, and how to fix problems with the work, and how to improve the work.

[00:23:11] Uh, that’s very powerful. And yet, uh, that’s, uh, takes some doing, right? What’s your

[00:23:17] Katie: parting words of advice for all the passionate lean practitioners listening in right now about how we can move to that next, next level and continue on and build, you know, really create that vision that you, you had 35 years ago?

[00:23:34] James: Well, first off, that this is never over, it goes on forever. Uh, so you should get used to that and it’s kind of a good thing. Uh, we can always do better. If you look around, you can see a lot of better that has happened, but never as best that has happened that’s as good as it could be. I think it benefits all of us who’ve been influenced by these ideas to realize, uh, A, we know this, but the world has to know, too.

[00:24:00] It’s not a program. This is not a one and done. Uh, our work is not over. Our work will never be over. That’s pretty good, though. Hey, what if I had solved all of the problems? Right now, as I wave goodbye, uh, there are no problems left for people to solve. Gosh, what a horrible world. So, I said, I shouldn’t do that.

[00:24:20] Yes. No, I should leave some problems for people to solve. Once I’m not around, and I’ve done that. And I have succeeded brilliantly. Okay? So, but look, it’s, it’s a matter of your time frame. And your notion of what work is. And so for us, work is about, it truly is about continuous improvement. Nothing we’re doing is ever good enough.

[00:24:43] By the way, nothing we’re doing will sustain itself. Every process that there’s ever been wants to get worse as bad as it possibly can. The only thing standing in the way is you and me and management. So this is an endless activity. There’s no point that you’ll ever be declaring total victory. And that’s good for you.

[00:25:06] Get used to that. By the way, when I said that Lean has failed to achieve what I had hoped it would achieve, but look, I had high hopes. Uh, like all young people, as I was then, you think you’re going to solve all problems on your watch. Turns out this has never happened in the history of the world, but nevertheless, young people believe that.

[00:25:24] Okay? So, now, and you’re young, by the way, I’m, I’m not, uh, I’m not, I don’t, I don’t fit that anymore, that description. But nevertheless, that’s not actually a realistic expectation. Nor is You know, declaring defeat and moving on, that’s not a realistic expectation either because the problems are still there and somebody’s got to deal with them.

[00:25:44] So, uh, let’s all keep marching. Uh, I think our lean community has proved to be pretty robust. Uh, we went through the euphoria stage at the front, and we’re way past the euphoria stage. And then some people said, uh, you know, I can’t do this, this is too hard, and I don’t know what they went off to do, but they went off.

[00:26:04] But the people who stayed say, whoa. This is every day’s hard, but the result is satisfying. If you do stick to it, let’s stick to it and we’ll just keep on going. And we’re never, ever going to get to perfect. Okay. Never get to perfect, but we can do better and better. That’s different doing better and better sustainably, better and better sustainably is different from perfect.

[00:26:28] But that is what, uh, as managers, our work is. That’s the actual work of management. So let’s keep doing it.

[00:26:37] Katie: What powerful reflections from one of the founders of the lean movement on what we’ve achieved and failed out with lean thinking and practice over the last 40 years and how we can learn from the past to adjust for the future as he passes the torch.

[00:26:50] Lean is still as relevant today as it was when Jim and his team introduced the principles and the term lean to the world nearly 40 years ago. The only secret to Toyota success. As 40 year Toyota leader, Isau Yoshino shared with me, and is the foundation of my book, Learning to Lead, Leading to Learn, is its attitude towards learning.

[00:27:11] So the secret to our success in spreading the adoption of lean principles and practices based on Toyota hinges on how we learn, how we practice, how we apply the principles. And how we learn and adjust from the past as well. Lean cannot be seen as just a set of tools applied to production only. It’s about how we focus on learning and focus on people so that we can create better and improve value for customers and for the world.

[00:27:39] What stands out most to me from Jim’s reflections, looking back and looking ahead over these last two episodes is the importance of lean being leader led, not delegated to consultants, either internal or external, and the need to embrace Kaizen and continuous improvement as more than an event, but rather a part of a connected management system based on learning.

[00:28:01] Lean has to be, as Jim says, a practiced practice. Practiced by all and embraced by leaders. As Jim highlights in these two episodes. Lean is about having constancy of purpose, always seeking ways to be better, whether through innovation or continuous daily improvement, and by creating systems and structures that allow managers and leaders to be coaches.

[00:28:25] It’s about growing a chain of learning in your organization. And that’s the purpose of this podcast, to strengthen our chain of learning together, to help us all learn and grow and get better so that together we can make the world a bit better each and every day. So let’s take up Jim’s challenge and stay focused and work towards achieving the vision he set out four decades ago.

[00:28:46] Reflect on Jim’s comments and advice for you as he passes this torch. What is one thing you want to do differently in your approach to organizational lean transformation? And what specifically can you do differently as a change leader or operational executive to ensure that Kaizen and continuous improvement is not something delegated?

[00:29:06] And instead is integrated into a full management system that is a practiced practice by everyone in your organization. If you really want to understand what Lean is all about, there is nothing like immersing yourself in the birthplace of the Toyota production system in Japan with a cohort of like minded Lean leaders from around the world on my immersive Japan study trip program.

[00:29:28] An added exclusive bonus is spending time with Toyota leader Asao Yoshino, who’s now in his 80s. To learn and talk with him about how you can unlock the secret of lean in your leadership and in your organization. Don’t take my word for it. You can hear about the impact of the program on many past podcast guests, including Isaac Mitchell in episode 32, Patrick Adams in episode 12, Stephanie Bursick in episode 30, and Brad Toussaint in episode 20.

[00:29:55] If you’re interested in joining the program, check out my website, kbjanderson. com slash Japan trip to learn about the next dates and the program details and submit your application today for the learning experience of a lifetime. Thanks for listening to this episode and special thanks to everyone who submitted questions to me for my discussion with Jim on LinkedIn and via my question form chainoflearning.

[00:30:20] com slash ask, especially the following listeners whose questions were featured in this episode. Stephanie, Sam, Sergio, and Astrid. If you’re enjoying this podcast, be sure to rate and review it on your favorite podcast player or YouTube by sharing what key insights you’re taking away from the show.

[00:30:37] Thanks for being a link in my chain of learning today. I’ll see you next time. Have a great day.

Subscribe to Chain of Learning

Be sure to subscribe or follow Chain of Learning on your favorite podcast player so you don’t miss an episode. And share this podcast with your friends and colleagues so we can all strengthen our Chain of Learning® – together.

About James (Jim) Womack

About James (Jim) Womack