Transform Your Approach to Problem-Solving Through Uncertainty

Do you ever feel like you’re stuck between chaos and bureaucracy, unable to break free from the status quo?

You are probably facing a common challenge that other leaders and change practitioners experience: how to navigate uncertainty while trying to drive innovation and agility in your organization.

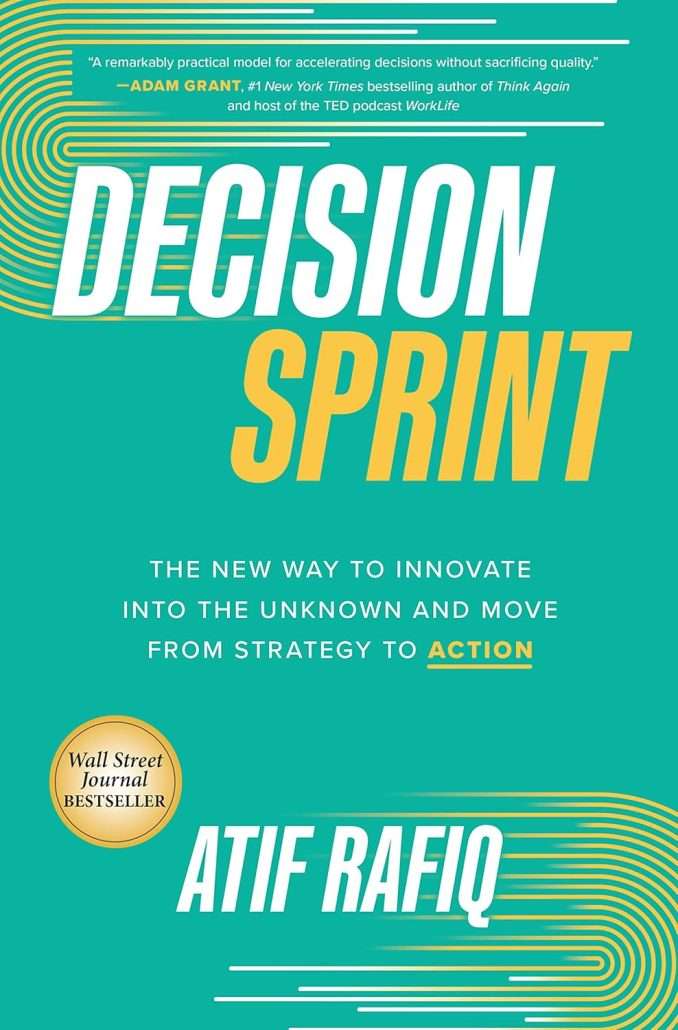

In this episode, Atif Rafiq, seasoned C-suite executive and Wall Street Journal bestselling author of Decision Sprint shares what he’s learned about leading through ambiguity to drive digital and cultural transformations at global companies like Amazon, McDonald’s, and MGM Resorts.

Atif breaks down the Decision Sprint framework to help you bring clarity into the unknown by moving problem-solving upstream, enabling you and your teams to make faster, smarter decisions that drive meaningful change and innovation.

Uncertainty IS what most organizations are facing today. Relying on outdated leadership models and approaches to problem-solving keeps you trapped facing the same issues year after year without real progress.

Tune into this episode and gain insights how you can break free from this cycle and embrace new approaches to navigate ambiguity and empower you to innovate and lead by making decisions faster, smarter, and better.

In this episode you’ll learn:

✅ The difference between boring problems vs. creative problems and how to bring authentic interest to solving the “boring problems” in your organization

✅ The risk in relying solely on “known” solutions instead of exploring innovative ways to solve problems

✅ Why organizations need to start thinking more upstream rather than focusing on what’s in front of them

✅ What the Decision Sprint Model is and how you can use it to get ahead of problems and move problem-solving upstream

✅ The difference between bureaucracy and chaos and how to avoid being stuck between the two

Listen Now to Chain of Learning!

Learn how to engage teams and deliver results while maximizing everyone’s time and energy in this episode.

Watch the conversation

Watch the full conversation between me and Atif Rafiq on YouTube.

About Atif Rafiq

Atif Rafiq has reshaped industries and generated billions in revenue for some of the world’s leading companies. He’s CEO of Ritual and has held leadership roles in tech companies like Amazon, Yahoo!, and AOL and has held C-suite roles at multinational corporations including McDonald’s, Volvo, and MGM Resorts. He is also the Wall Street bestselling author of Decision Sprint: The new way to Innovate into the Unknown and move from Strategy into Action.

Rafiq was the first Chief Digital Officer in the history of the Fortune 500, a pioneering role he held at McDonalds, and he rose to the President level in the Fortune 300. While leading business units, teams, and growth for companies, Atif has built a large following as one of today’s top management thinkers. Over 500,000 people follow his ideas about management and leadership on LinkedIn, where he is a Top Voice, and his newsletter Re:wire has over 100,000 subscribers.

Atif is passionate about helping companies push boldly into the future. He accomplishes this through Ritual, a software app revolutionizing how teams innovate and problem-solve, and through his work as keynote speaker, board member, and CEO advisor.

Reflect and Take Action

After reflecting on Atif’s insights, think about how you can make ambiguity more actionable in your organization. Consider using the concept of nemawashi—tilling the soil—by having more “non-decision decision meetings.”

Focus on framing the right questions, aligning stakeholders, and bringing them along on the thinking journey early.

Next Steps:

- Identify one specific action you can implement in the next two weeks to create conditions for better thinking.

- Step out of firefighting mode and resist being the leader with all the answers.

- Reflect on the outcomes and how it improves problem-solving in your team.

Leading through ambiguity is not about having all the answers—it’s about asking the right questions and bringing your team along for the journey.

Discover More in Atif’s Book Decision Sprint

Discover More in Atif’s Book Decision Sprint

If you found Atif’s insights on leading through ambiguity and decision-making valuable, dive deeper into his strategies with his Wall Street Journal bestselling book, Decision Sprint.

In this book, Atif outlines his framework for turning unknowns into knowns, accelerating decision-making, and driving innovation in complex organizations. It’s a must-read for leaders looking to move from strategy to action with clarity and speed.

Learn more and get your copy here: Decision Sprint.

Important Links

- Connect with Atif Rafiq

- Order your copy of Decision Sprint by Atif Rafiq

- Check out my website

- Follow me on LinkedIn

- Learn more about effective problem-solving in complex organizations: Episode 8: Wiring the Winning Organization with Gene Kim and Steven Spear

- Break the Telling Habit® and shift from being the expert to a leader who creates the conditions for problem-solving and innovation: Episode 13: 3 Ways to Break the Telling Habit® and Create Greater Impact

Listen and Subscribe Now to Chain of Learning

Listen now on your favorite podcast players such as Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Audible. You can also listen to the audio of this episode on YouTube.

Timestamps:

2:24 – Atif’s massive career shift and the challenge of changing the culture of a large established organization

5:51 – The risk of staying in a safe zone rather than navigating through ambiguity

7:52 – Boring problems versus creative problems and an example of the importance of taking interest in a “boring” problem

14:14 – The Decision Sprint Model and how it helps move thinking and problem solving upstream

16:21 – The role of experimentation in problem solving and the benefits of collaboration to gain insights

20:10 – Concept of alignment and how it connects exploration and decision making

25:57 – Difference between bureaucracy and chaos

29:11 – Upstream and downstream work and creating different systems for managing both

Full Episode Transcript

Atif:

I think the essential difference Katie is that, you know, chaos is really more personality driven, and that could be because there’s a very strong leader at the top. It could be because it’s still a founder led culture, and that’s not a bad thing. I love founders. But it could be a little bit more personality driven versus, like, systematic like, how do we decide what we work on, and look, it’s the priority, and the bureaucracy is like, you don’t really know who’s in charge, right? It’s almost like we’re doing things for the sake of it.

Katie:

Welcome the chain of learning with the links of Leadership and Learning. Unite. This is your connection for actionable strategies and practices to empower you to build a people centered learning culture, get results and expand your impact so that you and your team can leave a lasting legacy. I’m your host and fellow learning enthusiast. Katie Anderson, are you stuck between a state of utter chaos and the constraints of bureaucracy in your organization, trying to turn the ship around in the sea of uncertainty to become more innovative and agile, only to find yourself and your leaders stuck in the status quo, working on the same problems year after year. Well, it doesn’t have to be that way, and I’ve brought seasoned transformational leader and C suite executive Atif Rafiq to the show to help you discover how to lead change through uncertainty and ambiguity and get unstuck by turning unknowns into known sooner and moving to better decisions faster. Atif has reshaped industries and generated billions in revenue for some of the world’s leading companies. He’s held leadership roles in tech companies like Amazon, Yahoo and AOL, and has held C suite roles at multinational corporations including McDonald’s, Volvo and MGM Resorts. And he’s also the Wall Street Journal, Best Selling Author of decision sprint, the new way to innovate into the unknown and move from strategy into action. Atif knows a thing or two about leading people through change, solving important problems and creating value for organization. And he’s here to share what he’s learned along the way. We started off our conversation with a question about what shifts he had to make in his leadership and his approach to innovation and problem solving when he went from working in a highly innovative tech company like Amazon to joining McDonald’s as the first ever Chief Digital Officer in the history of the Fortune 500 let’s dive in.

Atif:

Well, Katie, talk about venturing into the unknown. I made a massive career shift where it was like switching from one planet to the other. So when I joined McDonald’s, as you said, as their first Youtube officer, in fact, the first in the history of the Fortune 500 I was coming into like a culture that was very different from Amazon, where I’d work previously, and I suspect that’s part of the reason why, you know, they were attracted to someone with my profile, is trying to bring in new ways of working. But at the same time, you know, that is a journey that’s a learning curve. First, we have to understand the current culture and how a big company like McDonald’s or Coca Cola or GM actually works today, and we have to sort of set a vision for what good looks like in terms of what is a different kind of higher velocity, higher innovation, higher risk taking culture, and then we have to work really hard to get it from one spot to the other. So that was a process that took years. It wasn’t a matter of weeks or months, sort of done one meeting at a time when I arrived at McDonald’s. The part that was actually simpler for me was setting the vision so the what, and the more challenging part was then the how, in terms of how we shipped the culture and the collaboration to get there, what

Katie:

was leading McDonald’s to bring in a Chief Digital Transformation officer in the first place, like, what problem were they trying to solve by hiring you to come into the organization?

Atif:

Basically growth after I joined, and it turned negative. That was the first time in maybe 10 to 15 years that the company had experienced negative growth. And so there was a real mandate, you know, there was a massive sense of urgency to do something strategic and to create platforms for long term growth. So for McDonald’s, you know, in the end, that what we came up with was really to think about convenience in a different way, and, of course, use digitization as a way to usher in a new level of convenience for customers, new ways of getting their food. And so really focusing on that pillar of convenience, which McDonald’s had been known for, but kind of had lost touch with, a little bit, and reformulating what that looks like for the digital age that was, that was the mandate. How

Katie:

is it moving from this culture where it was, you know, Amazon’s a really creative, fast paced, you know, more entrepreneurial culture, to one that’s more of an established, long standing, more probably traditionally run business for you as this, you know, tech entrepreneur, the

Atif:

difference is really the focus on the knowns versus the unknowns. You know, in a very established company, you know, you really get paid to make ideas bulletproof. Kind of from the beginning, and so you focus on the known commodities. Now that is a consequence, which is that you tend not to get into new territory because you get shy, because there’s a lot more unknowns than knowns. That’s where Amazon excels. And of course, other companies as well, is a comfort level with ambiguity, knowing that in the beginning, it’s really about a ton of unknowns, and what you should measure yourself by is the rate at which you’re kind of going into those rabbit holes, into those unknowns, making sense of them, coming back out, and then synthesizing like a point of view. Okay, we learned what we needed to learn, so we’re confident in recommending a direction that is remains bold when you focus on the known commodities, you’re likely going to potentially shrink down the idea that something very safe, so you’ll ship something, but it won’t really be a game changer. It’ll likely be a follower.

Katie:

Tell me more about that. You know, what’s the risk to organizations if they sort of stay in that safe zone and focus only on the known issues rather than navigating through that ambiguity?

Atif:

The key challenge I’ve found is actually cultural because let’s say you have a working team, and you have some senior executives, generally speaking, and they’re accountable for like this big set of initiatives or the strategy. In a traditional culture, you might have the expectation as a working team that you know all the answers in the beginning, and that when you meet with senior stakeholders, that you have to package up this bulletproof plan. You know which is, which is airtight, and the probability of success is like really high in a culture like Amazon, in the beginning, you want to get to that same spot. But in the beginning you’re you’re comfortable with a lot of ambiguity, a lot of questions, and so it’s okay in the beginning to say we defined the problem. We don’t have any answers, but we got a ton of questions, but at least we think these are the right questions to explore. And people nod their head and at Amazon, that’s progress, and then they say, come back in two weeks. Where are you on going down the rabbit holes and looking at these questions and making sense of them, what did you find out? What did you learn? What’s your takeaways? What are your conclusions? And that’s sort of your second touch point. And by your third touch point, of course, you’re expected to have some really confident sort of recommendations that you can defend and put on the table. But the difference between that and the traditional culture is that your ideas probably remains elevated in a big one, because you didn’t shy away from the unknowns. They’re actually factored into your thinking. You never shrank it down in the beginning to the known commodities, and that’s quite a different ambition, if you

Katie:

will. Yeah, there’s a comment you may or actually a phrase that you have in your intro that says problem solving needs to be reinvented for the modern era, and solving for the unknowns is the key. Because really, our world is so ambiguous these days that if we rest on only the knowns, we’re really going to get stuck. You talked to me about the difference between boring problems and creative problems. So Atif, what are boring problems?

Atif:

Boring problems are ones which probably matter a lot to customers, and that customers can feel but they don’t win you any awards in terms of being the most innovative thing to ship, so to speak. So an example would be, I thought I joined Volvo cars, where I moved to after McDonald’s to work on things like autonomous vehicles and connectivity and all the cool stuff that was coming down the pipe towards the end of the 2000 10s. And I was but when I arrived on the job, literally my first day, they told me that the main factory in Sweden was shut down, and it was the software glitch that was the cause of the problem. And so the XC 90, which is the money maker, the cash cow for the company, we weren’t producing these, these vehicles, and customers really wanted them. And the factory was shut down for two days, and that was costing the company millions of dollars. Now the software in the manufacturing, you know, site, you know, it’s old school stuff. It’s COBOL. It just, you know, it does boring stuff, right? It moves things down the assembly line. That took priority, obviously, I dropped everything and we spent, I spent my first two weeks with a crack team getting our hands dirty and looking into why this was happening, not only some short term fixes, but really the root causes. And the beauty of this situation was kind of like turning, you know, a lemon into lemonade, where, basically because we were able to give the attention and energy to a very customer, you know, business oriented problem, and get the company to the other side, and create a lot of credibility. So then later, when it came time for the big ideas around autonomous vehicles or connectivity or other things like new ways of thinking about importing and in the car, our team had credibility that we would focus not only on the sexy stuff, but on the other things that. Matter. And so I think boring problems have a lot of value in terms of signaling to the culture that when it comes times for innovation, that there’s a level of trust.

Katie:

You made a comment to me that leaders need to start bringing more authentic interests to those daily boring problems, so you can then focus on the creative problems to keep innovating and moving the organization forward. What have been some more of your like shifts that you’ve had to make as you’ve evolved as a leader? So one is to get more authentic and interested in those boring problems. What are some other changes that you’ve had to make back

Atif:

on the boring problems? It’s like having two children. One is innovation and one is the boring children. You got to love your children equally, right? Katie and so if you’re going to have deep curiosity, deep intensity around problem solving, apply it equally. That’s really, really powerful stuff. It’s also more inclusive, because if you have a large team, you know, let’s say several 1000 employees, you know, you don’t, you don’t want to give a sense that they’re the chosen ones that work on innovation, the other ones who just keep the business running. But coming to your question in terms of some other leadership insights that picked up along the way. One was the idea of the role of the leader, focused on calibration over control. And let me break that down a little bit. The higher up you go in a company, and depending upon how progressive they are with their management approach. A lot of times, people come into the room and they expect to be order takers, so they’re expecting the leader to know exactly what she or he wants, and they they, they’re looking to serve that up and go executed. Now, the problem with this is that the leader is one person. They don’t have all the information, and sometimes they’re not close to enough of the details. So really, the job of the leader is to kind of really calibrate the brain trust. It’s why we have the working team. It’s why we have the talent in the organization. And really help calibrate. How are they defining the problem? What questions do they think are important to look into. What did they find out? How did they synthesize them? What recommend conclusions are they drawing? How did they get there based on that when actions are necessary? I mean, it’s not knowing all those things. It’s actually calibrating how the team is thinking about them. Are there blind spots? Are we elevating our thinking? Is there someone in the company we can go get input from to do a better job of those things? That’s what I call calibration, and my leadership evolved towards really a high calibration model, and to the point where people would be like, we met with him and he doesn’t have any answers, you know, like he’s not telling us what to do. And of course, that’s partially true and partially not true. It’s just more about enabling teams. And I think good leaders enable teams.

Katie:

I talk with so many leadership teams that we have to make this shift from being the expert with all the answers to in your terms, being the leader who’s calibrating creating the conditions for people to bring forward their their ideas and to problem solve and develop their own expertise around that. I call it breaking the telling habit, because, as you said, like people expect you to have the answer in this leadership role, and maybe that’s one of the misconceptions of what leadership is, is that the leader has to have all the answers, versus what you’re saying here is creating the structures and the calibration opportunities for problem solving

Atif:

in stable environments where things didn’t change over decades. That was probably made a lot of sense, because by being a veteran, so to speak, of the company or industry, you kind of saw everything. And the current situation probably is, you know, is a strong fit of what happened in the past, but today that’s completely nonsense, like things change so fast just because you were focused on something six months ago doesn’t mean that, you know, you know all the the kind of like contours of it today. So you really have to be hungry for input. You have to be obsessed for input. Good leaders are obsessed for input, not because they don’t know things, but because they’re they they don’t want to miss the knowable unknowns. That’s the job. We have to get the knowable unknowns on the table. Once we do that and put it in the middle of the table, we have the right talent, the team will make the right sense of it.

Katie:

So let’s talk about how your thinkings evolved into your decision sprint model, and this understanding of how you can navigate through that ambiguity better and move some of that thinking more upstream, rather than just focusing on the knowns that are right in front of us. Sure. Well, I

Atif:

wrote the book decision sprint, and it’s mainly about the idea of upstream work, which is essentially the starting point, maybe a raw idea or an objective. And we have to get to a decision point, because only after decisions are made, and there’s some degree of buying Can we move on to execution. So it’s not really a book about execution. I think there’s a lot that’s been written about that. And some cultures are really strong on that part. I think those cultures tend to struggle with the upstream part, which is essentially. So how do we, you know, shorten the time and just keep you know, more effectiveness in the winding road of getting, you know, from a promising idea to unlocking buying and decisions, and that’s really upstream work. And the core thing that I focus on there, there are several things, of course, involved in upstream work several stages, but one of the ideas I introduce is the idea of purposeful exploration to take a step back. You know, have, I think we’ve all been in situations where there’s a rush to judgment. Someone has a promising idea, someone said, walks in the room and says, Wow. You know, McDonald’s, we should do a subscription for coffee, and some people love it. Let’s go make it happen and test it and move to experimentation. Other people hate it, and it’s just a lot of judgment and arrest to opinions. What we should do instead, it, before we try and align on any of those perspectives, is actually build and run purposeful explorations. What are the key things? How are we framing the problem? What’s the breadth and depth of kind of issues and questions we need to get our head around and make that a thing, like a workflow, and then use that as the basis to to formulate the recommendations. And so a lot of decision sprint breaks down the notion of upstream work into certain stages, the first of which is exploration.

Katie:

And what I’m really hearing too is like, we have to first understand what problem are we trying to solve, right and and then have that experience exploration and maybe some experimentation around there too, to understand are we even having, you know, is our thinking even moving in the right direction? How? How have you gotten more comfortable with experimentation and that sort of learning process or exploration process in that upstream environment? Well, I

Atif:

think experimentation is a double edged sword. Sometimes it’s actually a crutch. I would say, if you’re in a tech company, if you’re at Google or you’re a meta, experimentation is actually a crutch because it seems like you’re really busy and you’re doing the right things, because you’re trying to get data, and who’s going to who’s going to argue with, Oh, we’re getting data to make data driven decisions, right? But like, what is the question your experiment is trying to answer, and is that the most fundamental, or part of the core fundamental questions related to the problem we’re actually trying to solve. Often you find it’s not the case. It’s like somewhat adjacent, you know. So it’s interesting data that you’ll get from the experiment, but it’s not going to put the team in a position to say, yeah, for sure, we have a lot of clarity. Let’s, let’s roll this is, this is what we should be building. On the other hand, if you’re in a culture where there’s no experimentation, right, then that’s not a good thing either. So it’s really finding the sweet spot of by defining the problem correctly and first coming up with the right set of questions and then looking at how those questions are best answered, and sometimes as an experiment. And guess what? Sometimes it’s even faster than experiment. It’s common sense, it’s institutional knowledge, it’s a brain trust and a conversation. Those are also very important forms of collaboration, and in terms of getting insight, that

Katie:

makes a lot of sense. There is sometimes, like, once you’ve defined that problem and done some thinking around it, there is that just do it sense. Like we actually know the answer to this? We don’t necessarily need to do a lengthy experimentation. And I think this is tension in some of the organizations I work with that are trying to develop more of a problem solving culture, as you just shared. Is that tension between wanting to create more experimentation and more problem solving, but not also pivot so far that we’re not actually taking action or really making those decisions?

Atif:

Yeah, for sure. I mean, we talked about an example of a coffee subscription for McDonald’s, and the instinct may be to operationalize it. Hey, can we make it work in the drive through? Hey, how would I redeem it at the counter? Is the crew trained on to know what the heck I’m talking about, and punch it into the POS? You know, all those things, very operational. But what are the merits of this idea? And I would tell you straight up that it’s not because McDonald’s wants $20 a month for coffee. It’s because they want some of the times people do that for those same people to go get a sandwich, because that’s where the money is. And so it’s about the cross sell, if you will, or the incrementality of the food purchases. So if that’s really the main thing, make the main thing the main thing, how do we get our head around whether you know that’s going to happen or not? And that could be a different type of experiment or test. It may not be a customer facing test, right? It could be more some marketing analytics thing. Or, you know, there may be another way to get, you know, some signals and some clues as a as to whether or not that will happen. And so we first want to set the parameters right, and then we can go crazy with, you know, different forms of acquiring data, you know, so that we’d be more competent,

Katie:

you know, as exploring your book and. One of the concepts you talked about moving this upstream work is connecting exploration, which we’ve just talked about, and then alignment beat so we can make better decision making. So talk to me a bit about the concept of alignment and how you have connected that exploration and decision making through alignment as an executive in your organizations, well,

Atif:

I’ve had a frenemy relationship with alignment, and we’re more on the friend side, but before we weren’t. And the reason is because, when I moved to Amazon, to some of the well known the fortune 500 I would often, after we had a promising idea, someone on my team got a big idea. You know, maybe a peer of mine, very senior in the company would say, hey, Octave, do you have a second I really want, want to align on things. And I would say, Sure, yeah, alignments, amazing. Let’s do it. And so we’d sit there in the hallway. And eventually the takeaway was, how do we shut down this idea your team is crazy and this is going to break the restaurants and our PNL or something like that, you know, they kind of get carried away with the idea before at the embryo stage right, and it’d be like, Hold on one second. You know, you’re kind of making a ton of assumptions here. And if we made different types of assumptions, it could be a real winner. And we don’t know either way. So let’s, let’s find out, you know, and how can we best find out? And so I went through a stage, to be honest with you, 11 years in the C suite of the Fortune 500 where at first sight said, I’m banning alignment. I don’t want to hear this word. It’s a bad word, and it means shutting things good ideas down. But then I realized that’s, you know, alignment can actually be powerful if we leverage exploration and we come into the alignment step with some high quality detective work, right? Because alignment is actually important. So I was wrong, because alignment is what gets enough people nodding their heads and the buy in is really essential for great execution. When people believe in something, then they’re going to do a 2x or 3x 3x better job of the execution. So it’s worth showing them how we arrived there. So if we have purposeful exploration, we’ve kind of come up with the right recommendations people understand how we drew those conclusions, then that is a step worth taking. So in the book, I talk about how to, you know, prepare for alignment. You know, what, what kind of package you put together to get people aligned once you have a high quality exploration. You know, it could be something like a strategic narrative, like the narratives that Amazon does. But it doesn’t have to be that’s just one form or medium. There’s a lot of ways in which you can package things together to have people follow the thread of how you’re right, that what you’re suggesting as the direction of the idea or initiative,

Katie:

and therefore then making the decision at the organizational level of which way you’re going to go, but hopefully in your direction.

Atif:

And often, to be honest with you, Katie non decision, decision meetings, which are the best ones? And I’ve been in those, and I love them, and I knew they were going to happen because I was very confident in the upstream work. The people we hire in companies are there for a reason. They’re usually very bright. They know their stuff. They’ve seen a lot of things over the years. So, you know, if they see the right thread, they see the work behind it, how we got there, they can follow it, and it’s a calculated bet they’re going to go for it, you know. So there’s so many non decision, decision meetings where it’s not high stakes because we did the right upstream work. And that’s my hope for for people in teams. That’s

Katie:

my hope as well. There’s a Japanese word that’s NEMA washi, which means tilling the soil. And it’s exactly what you said here. It’s the it’s all of the the work before the meeting. So you’re not actually, truly making it’s that no decision, decision meeting, because you’re you’ve already really brought people along on that thinking journey. It’s why Toyota has been so successful in using a document called a three thinking because they it’s it’s sharing all the thinking and taking people on that, that exploration journey of defining the problem. How are we thinking about it? What are the things we’ve done so that the alignments already happened before you’re getting to the meeting? And it seems like that’s a big counter intuitive thing to a lot of, I guess, American and Western companies. Well,

Atif:

it’s so powerful. In fact, I’ve been in the best cases, what I see is you spend like, two minutes on the decision, because it’s everyone’s already in agreement, and you literally spend the rest of the meeting talking, accelerating the execution. So you’re like, Oh, what do we need to move around? What dollars can I move from here to here to allow this to happen? Okay, so you start actually accelerating the idea and the execution quite a bit. It’s a really funny human dynamic, to be honest with you, because a lot of times the the team that’s accountable for the idea or the product thought they were going in to get a yes or no, but they’re, i. Actually getting a ton of help of people, like, clearing the way for them, and that’s a really great feeling. That’s

Katie:

NEMA washi done, right? Or all of that alignment work that you are talking about, like, that’s bring it upstream so that at the meeting, we’re actually talking about what we’re gonna do with it, and how and how to move forward 100% Yeah, I was reading your book, and I was really struck by a phrase in there. It reminded me of a visit that I had recently to a tech company called Mendel innovations and talking with their CEO, rich Sheridan. And it was something you said, almost something that was almost exactly what he said, too, that without a method for handling upstream work, companies must choose between bureaucracy and chaos. And he had a diagram that as a tech company, they were constantly trying to either navigate between bureaucracy and chaos, and it just felt stuck. And so I thought that was a really powerful, similar comment that you made. So how do you see the difference between bureaucracy and chaos, and how can you avoid being stuck in between those two? Well,

Atif:

I think the essential difference Katie is that, you know, chaos is really more personality driven, and that could be because there’s a very strong leader at the top. It could be because it’s still a founder led culture, and that’s not a bad thing. I love founders, but it could be a little bit more personality driven versus, like, systematic, like, how do we decide what we work on and what gets the priority and the bureaucracy is, like, you don’t really know who’s in charge, right? It’s almost like we’re doing things for the sake of it. So, you know, we did these three things last year, and these three things will continue. And here’s their, you know, the project plan, and then you start, you’re able to poke a lot of holes in there, and you can’t connect those things to the higher level purpose of the organization, their strategic pillars, and how we connect and cascade the work that we’re actually doing within a given team up through that. And you know, you should be able to do a good amount of that. That’s not always possible, but you should be able to connect it to the higher level purpose and objectives. And then, you know, the other feature bureaucracy is one where it’s just very difficult, where the plans are set out well in advance, right? So the plans are actually perfect from the beginning. And so there is not a really appetite in the bureaucracy for exploration, because everything has to add up all the time to a near certain outcome, right? So we’re not in a different type of environment, you know, we’re not as much outcome focused in the beginning, you know, we want a huge outcome, but we’re really trying to understand the problem and so some comfort level with exploration of the problem space. You know, we need to find that that middle ground.

Katie:

A lot of the organizations I work with are in these, like large bureaucratic organizations like healthcare or government, you know, organizations where as a lot of those policies and procedures are put in place because they’re trying to control the chaos. But what I’m hearing from both you and rich Sheridan is like, if we can move the upstream work to get better at decision making, we’re going to actually be able to remove more of that chaos and the bureaucracy at the same time.

Atif:

Well, healthcare is an interesting example, because when something is scaled out to patients and lives are involved, you know, we want a really high level of precision, right? So we want some of the, you know, that stability and the controls. Now it’s the question is, like, before we get there, before we’re scaling something or rolling it out, you know, we want a different system. So there’s a system you need for execution, which I fully agree needs high level precision and control and more more like guaranteed type of outcomes, like these mistakes won’t happen. And then there’s a system that we need before we get to decision points when something is still essentially like trying to be understood, and the direction is trying to be said, the decisions haven’t been made, you know, the acts, the plans are not set yet, and that’s a very different model. We don’t want to use an execution system to manage the the upstream part. So just even recognizing the difference between upstream and downstream can be very powerful and have a system that’s fit for built for purpose, for each one, I think, is a huge unlock for organizations.

Katie:

How can organizations start getting better at making that, that recognition, or that difference between upstream and downstream work?

Atif:

Basically, they, you know, they should start with their strategy, you know, and they know their strategic pillars. They’re usually able to break those down into several, key initiatives, and then that’s where they should start. So the new territory essentially like, oh, we know we can be the same as last year if we just do things a little bit better, but we’re not going to get that 10% or that 5% or that 20% unless we start getting some of the new things to land so that. Really where we should focus on putting in the upstream systems. Now, some companies have different names for that. Some call it innovation, and some that’s just regular sort of product development. The labels are less important, but it’s the new territory, the problem solving frontiers that if you cross those frontiers, well, you know, there’s going to be huge value. That’s where you need to put in an upstream system and approach

Katie:

and making that connection. Then to, you know, there’s the creative problems maybe are more upstream, and the boring problems are downstream, perhaps. And how do you balance those two as well? Am I? Am I right in making that, that connection, or do you see that differently?

Atif:

I think, you know, the boring problems can have a lot of ambiguity as well, you know. And we’ve got to also remember that, you know, every new idea after its birth, and if it takes flight and is launched, you know, has a shelf life of years and years. So there’s always some problem solving horizon for an idea. And so the idea of continuous exploration is also powerful. So just kind of tie a couple things together. It’s not just about launching an idea or a brand new idea. You might be in your form of an idea. I mean, when I think about Volvo, we launched a subscription for cars. They’re all inclusive. Include the insurance and everything else you know, and you can get it from your phone and have it delivered to your house, so you didn’t have to go to the dealer. You know, we launched that in 2018 it’s now six years later. And when I talk to people in the company, they have problems that are, you know, really, really interesting, really meaty, really meaningful, that they need to get their head around. So it could be years into an idea and still have some frontier. It’s always the next wave of elevating that idea. But I do think it includes the boring ones for sure. Thank

Katie:

you for elaborating on that. I want to end on this one quote that you have at the end of your book that really can like stood out to me, because it is the challenge, the number one challenge that leaders across the globe share with me that really inhibits problem solving, I guess, whether it’s the boring problem or the creative problem in their organization, but they don’t have time for problem solving or to support their teams in problem solving, because they’re firefighting all the time, just running from problem problem putting the fires out, and your quote is a company of firefighters can at best maintain the status quo. So what’s your suggestion for how leaders and practitioners can get out of this firefighting mode and actually move beyond the status quo?

Atif:

You know, the C’s do part from time to time in corporates, corporations where the seeds part and you don’t have a firefight, or several of them going on, and that’s your opportunity to really say, Okay, what is strategic, what is ambiguous, what could be something that could grow into something really amazing. And now, how do I kind of roll my sleeves and work with the team. Enable teams to do some really interesting problem solving around this. Give, you know, work with them, calibrate the word, give them psychological safety, give them space, give them some cover, and then plant those seeds. So, you know, we alternate between, yeah, firefighting and planting seeds, firefighting and planting seeds. And so, you know, just a reality of working in a corporation is there may be, you know, extended periods where you don’t have the time to plant the seeds because you don’t want the plate the forest to burn down. I totally get that. But those, those windows of opportunity do come up, and we have to take advantage of them. The good news is, when we plant those seeds, we’re really surprised. A couple months later, crack team, and what they’ve come up with, what that’s grown into, it’s really powerful. And then other people see that. Other teams see them. They they want to be in that mode as well. It’s a lot of great oxygen for them. So they start figuring out, well, how do I bring that into my way of working. And it can be a very powerful thing that adds up over time.

Katie:

And it can be something simple too, you know, like asking just a few more questions, or giving a little bit more time for someone to think, and not just like rushing in and always giving your answer, just like pausing a little bit. So it doesn’t have to be this huge, huge leap for this whole creative like thinking space. But how do you start creating those little, maybe micro, micro moments for thinking and problem solving and creativity? And

Atif:

that’s well said, too. Katie, you know, it’s a different mode. So just recognizing the mode you need to be in with the people you’re with, because you’re in a Zoom meeting or a real meeting room, whatever, and people come in as firefighting, and you’re carrying that mode over to the next one. You know you don’t have to do that. You know you might be with a team that actually has more space and more capacity for critical thinking and creativity. And so now you need to make that shift, and you need to become a look your parenting style. All needs to shift. Let me put it that way,

Katie:

as I always say, the best leadership learnings I have is through parenting and practicing how to parent my children. So apply it at work as well. Thank you Atif for coming on chain of learning and for sharing your insights about your book, for that are included in your book, decision sprint and from your years of leadership and experience in a multitude of different types of organizations.

Atif:

Katie, it’s been a pleasure joining you. Thanks so much for having me.

Katie:

Uncertainty is what all of us are facing in our organizations and our lives today. Relying on old leadership and problem solving approaches that are based on certainty and the knowns will only keep us stuck in the status quo, firefighting and trying to solve the same problem unsuccessfully year after year. Atif shared so many examples and strategies in this episode about how you can become a more effective leader by navigating unknowns and getting to decisions faster, what he calls the decision sprint as change leaders, whether you’re an executive manager, team member or change practitioner, your ability to move decisions upstream and to enable faster decision making will be the key to your success in getting the results that your company needs. I encourage you to check out autifs, Wall Street Journal, best selling book, decision sprint for even more stories, frameworks and tactics about how you can navigate ambiguity and move from strategy to action and to connect with Atif on LinkedIn.

I’ll put the links in the full episode show notes, and if you haven’t already listened, I also recommend going back to Episode Eight of this podcast, where I talked with Steve spear and Gene Kim about strategies for effective problem solving and innovation in complex organizations and their book wiring the winning organization, as well as listen to episode 13, where I dive deeper into how you can break the telling habit and make that shift from the expert with all the answers to a leader who creates the conditions for problem solving and innovation through asking better questions. Reflect on what Atif and I discussed in this episode about how you can start making ambiguity more actionable in your organization.

How can you conduct that tilling of the soil the NEMA washi so that you can have more non decision decision meetings by asking decisions, framing the problem that needs to be solved and aligning your stakeholders sooner by taking them along on the thinking journey. Identify one action that you can take in the next two weeks to create the conditions for better thinking and get out of that constant firefighting mode or being the leader who has all the answers, then put it into action and take time to reflect on how it goes and how what you’re learning is contributing to better understanding of the real problems that you need to solve for yourself, for your teams and for your organization.

If you’ve enjoyed this episode, be sure to follow or subscribe now to chain of learning and share this podcast with your friends and colleagues so that we can all strengthen our chain of learning together. And if you’re enjoying the show, please rate and review it on your favorite podcast player. Thanks for being a link in my chain of learning. Today, I’ll see you next time. Have a great day. Bye.

Subscribe to Chain of Learning

Be sure to subscribe or follow Chain of Learning on your favorite podcast player so you don’t miss an episode. And share this podcast with your friends and colleagues so we can all strengthen our Chain of Learning® – together.

Discover More in Atif’s Book Decision Sprint

Discover More in Atif’s Book Decision Sprint