New book: The Lean Strategy

As I mentioned in the Gemba Academy podcast released two weeks ago, the most recent business book that I have read is The Lean Strategy by Michael Balle, Daniel Jones, Jacques Chaise, and Orest Fiume.

Michalle Balle, the lead author, agreed to answering some questions for me to share with you. We have continued to have an interesting and thought provoking dialogue over the past two weeks about the book, Lean as a strategy, and Lean leadership in general.

Michael Balle’s answers to my the three questions of our interview can be found in my post Book Review and Interview with Michael Balle on “The Lean Strategy” – Part 1 – Is Lean a strategy?

Read on to learn what Michael has to say in response to my other four questions – including reflections on his personal Lean journey.

Win a free copy of The Lean Strategy

The book giveaway has now closed. Congratulations to the 3 winners of The Lean Strategy by Michael Balle, Daniel Jones, Jacques Chaize and Orest Flume book giveaway.

The book is also available on Amazon to purchase directly or more information can be found here.

Interview with Michael Balle about The Lean Strategy

And without further ado, here is the rest of our interview.

4. An important point you make in The Lean Strategy is that Lean is about changing leadership habits, mindset, and way of thinking. What have you found to be the hardest personal shift in mindset or habits for leaders to make?

It’s clearly understanding that your team makes the result, and doesn’t just execute your plan: who’s in the bus really matters. One dimension we don’t insist upon much directly in the book is that by expecting constant “next step” action from people, lean thinking also leads to having a completely different idea of who knows how to learn, who can try new stuff, and who has sensible judgment – and who not. In other words, discovering who in the company contributes good thinking, sensible, concrete ideas and suggestions about facing our challenges.

The biggest challenge I encounter is first, obviously, to get CEOs to face strategic challenges they don’t want to look at (mostly they know they should but they don’t have a solution at hand) and secondly getting them to realize that they need to find the right person to work with, and it is not often the person with the title or the role in the organization.

In my experience, this is what CEOs struggle most with. They tend to assume that if they keep doing what they’re good at with the people in the current roles, things will work out in the end – and working backwards from what kind of overall goals do we have, who can help us with them and then, and only then, discussing how to get there with the people is a big change of mind.

5. What has been the hardest personal shift in thinking or behavior that YOU [Michael] personally have had to make as a Lean leader /coach/ practitioner?

When my father retired in 2001, I had just completed my PhD, published four management books, ran “lean” workshops for the Renault Institute whilst teaching organizational development in business schools, as well as helped him on the development of three full scale “excellence systems” – I thought I knew what I was talking about.

We then started building a program for an automotive supplier (an “excellence system”). He talked to the CEO and I worked with a community of practice of plant managers. I had them looking at indicators, tracking daily production analysis boards, doing 5S and solving quality problems, we had quick early result. My father kept suggesting that we should move to pull and… I simply did not know how to do that. I insisted we didn’t really need it.

After months and months, I had to admit the results we had were fragile and kept coming and going according to events and the plant manager’s motivation. I learned how to set up a pull system.

The lesson was both painful and profound. I realized that in all my previous work I had been cherry-picking: assuming there were some interesting aspects of lean I should learn about and integrate in my personal understanding of performance management.

I then changed my mind and realized I had to learn lean as a full system. And keep learning it.

Which is how I got to write The Gold Mine – the idea was both to capture my dad’s career experience and show that I had finally understood enough of this lean system to be taken seriously.

Two things happened.

First, I missed the central point of built-in quality: it appears at the beginning of the book and at the end, but kind of disappears during most of the narrative – so more to learn on the system front (and then more again with flexibility). This seems obvious with hindsight, but hard to see when you’re in the thick of it and grappling, as anyone does, with motivated thinking (anchoring on a conclusion upfront and justifying it through reasoning). And here mentors help greatly.

My father was always going on about quality, sure. But I was very lucky that Dan Jones took an interest in The Gold Mine manuscript (and indeed, pushed it through to publication), and we had deep discussions of why and how the lean movement had latched on to flow, but had so little to say about value and quality – to this day, there is not one book focusing purely on Jidoka (Art Smalley and I tried to write a workbook on built-in quality, and eventually failed).

These talks with Dan were absolutely key to seeing my own blindspot – which was the result of having been trained as an academic and consultant, and having a process rather than product perspective.

Second, I realized that the narrative form of having it as a novel was not incidental. Most readers assumed that I was using the novelized form to make the tools more palatable, easier to understand in context. But, no, this is not what I wrote. The story is the story of Phil Jenkinson’s company transformation through Phil learning to use the lean tools – and being transformed himself.

The tools are just tools – they need to be applied by someone to a something. This is the story that matters: how you learn to see things differently, so you use the tools differently, which transforms the company.

This realization led me to take a second deep turn and apply the lean tools I knew to my own work as a writer and a consultant – the result was unexpected as it profoundly changed both my writing and consulting practices, to the point that I can’t quite describe what I do as a consultant to others before the conversation stops in mutual irritation.

Customers are not “one more project” to find to support the turnover and the bottom-line. They’ve become friends I try to help to make more money, to do so better than any other consultant if I can and to stick with them through good times and bad times (in particular, staying there to face the consequences of whatever we’ve implemented together). As a result, they also help me when I need help with the lean movement – and with tolerating my prices, to protect my writing time.

I now try to force myself to apply any new tool I learn about to my own activities before discussing it with a CEO – which led me to realize that if I wanted to understand Hitozukuri, I first had to learn Monozukuri and make the effort to figure out the products and services the companies I worked with did.

Again, none of these realizations happen easily – or on one’s own. It’s easy enough to describe after the fact, but on the day, the struggle in the fog-of-war is often overwhelming.

I was very lucky in meeting Jacques Chaize who, after a mixed experience with “lean” driven by a top consulting firm, had the patience to explore with me what “real” lean could mean for him and his company. His patience and open mind was essential to step away from a programmatic “use the tools to do something to people” approach to gemba walks, and “let’s find out what we can with people so they take initiative themselves.” Luckily we had similar backgrounds in systems thinking and organizational learning, so we figured out (rather slowly) that a key feature in lean was learning within the daily work, mostly with the tension between just-in-time and jidoka, as opposed to in “learning labs” or “workshops” or “training” – out of context. Jacques mentorship was essential to first, learning intervention exclusively built on gemba walks, and second, learning to talk to CEOs.

As I did this, my father’s lessons on “the helicopter” really came home and I find myself complementing his training on looking always more precisely into technical details with learning the basis of finance and valuation to understand the bigger picture of the problems I see CEOs struggling with.

Which is how I came to see lean as a full strategy. Although the CEOs discuss strategy on the gemba, I never, ever give any strategic advice – how could I? But we go back to the TPS and go through every step and try to figure out what it means in this case, and, yes, come up with new places we’ve got to check and new ideas we need to try.

The idea that we’re going to grow profitably and sustainably by building the right products the right way by involving every mind and heart in the business in this effort is a distinct strategy, just as service excellence, reducing costs line by line in the budget, using new technology to disrupt market, squeezing all value out of contract negotiations with partners, or breaking down supply chains to find the lowest cost place for each component are alternative strategies.

Honestly, sometimes the lean strategy seems more like a spiritual battle than simply a strategy in a world where screwing someone for short term gain seems to have become the accepted way of doing business or running organizations – even in government or NGOs.

Which brought a new realization – I was completely underestimating the importance of teamwork with the lean worldview.

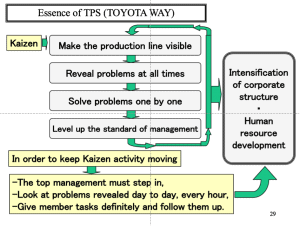

To the right is a slide I often refer to from Mr. Nampachi Hayashi, my father’s sensei:

I often wondered what “intensification of corporate structure” could possibly mean but the more I work with CEOs trying to align their corporate structures with their lean strategy, the more I see the importance of teaching people to solve problems across functional boundaries and to get corporate to create enabling systems that support frontline employees, as opposed as run projects from each of the professional cultures (IT, Finance, HR, etc.) for no other reason than they really, really want to do it.

Glberto Kosaka, my sensei in Brasil, just expressed it brilliantly: rather than a chain-of-command, we need a chain of help. How do we get corporate to help?

Still, the one shift that is currently facing me from continuing to learn lean, and which I struggle with just as I did with these other changes, is the fact that Toyota has been leading not only in green products, but green processes as well (I’ve got documents from the 1980s that showed how they intended to do so).

This is clearly the issue of our days, and I’m not doing enough – personally, first, and then to lead the lean movement in this direction.

Challenges keep coming, and much kaizen is needed at every step. This is one lean lesson that doesn’t seem to change.

6. This book is the result of collaboration between four authors. What was one concept or idea that the four authors did not share the same opinion on initially or that you had to spend some time on to get to consensus?

How to calculate inventory turns.

7. What is a question that you haven’t been asked about “The Lean Strategy” (by me or anyone else) that you would like to answer or a comment that has been made about the book that you would like to respond to, and what is your answer?

Most questions I tend to get about The Lean Strategy are about whether lean is a strategy or not (which I find strange because anything that is about aiming for overall goals through a specific plan of action is a strategy, per definition) or some specific parts of “tool lean.”

The book actually is mostly about innovation, with the very specific lean angle of Value Analysis/Value Engineering and the core concept of reusable learning (as opposed to reusable knowledge), and the cases describe in details cases of technical innovation which no one seems to pick up on.

The book also presents the financial model of lean, and, if we push it further, the fact that management accounting ignores the costs of poorly used balance sheet (non quality costs, inventory costs, asset under-utilization costs and so on), which leads to over investment and then absurdly reducing running costs – and the absurd situations we see every day.

In every sense this book is to me about showing there is an alternative to financial management that is customer and employee centric and the way towards sustainable profitable growth – as well as the way to design and manufacture greener products with greener processes.

So the real surprise is that few of the commentators seem to be catching on the much bigger promise of lean that we try to highlight. Which just tells us we need to write it better next time!

———————————————————-

What do you think?

What do you think about Michael’s comments about Lean as it relates to strategy, innovation and personal transformation? Please leave your comments in the section below.

And don’t forget to register for the GIVEAWAY – sign up for a chance to win your own free copy of the book!