As I shared in previous posts, Toyota Memorial Hospital (TMH) has been practicing parts of the Toyota Production System (TPS) for many years.

However, the depth of TPS practice is not as advanced as many might assume for the hospital owned and operated by the Toyota Motor Corporation where TPS was developed.

In these earlier posts, I described more of the “invisible” parts of the Toyota Way – the focus on the people – that TMH is leading with.

But what did I see in terms of evidence of the tools and the production principles in action?

Hospital and clinic tour

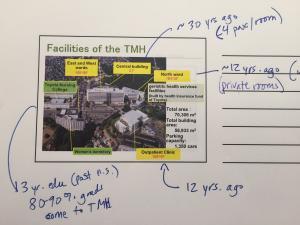

For one hour of our four-hour visit, one of our hosts took me and Mr. Yoshino, my friend and retired 40-year Toyota executive who was serving as my interpreter for the day, on a tour of the facility.

We saw parts of the hospital and outpatient clinics including the supply room, the call center, the new CyberKnife surgical suite, and parts of the outpatient facilities. We did not get to see any inpatient clinic areas or direct patient care being conducted.

We also had additional discussion time where Mr. Sumiya shared aspects of their kaizen and hoshin kanri (strategy deployment) processes, which I’ll write more about in a future post.

Due to language translation needs, I know that I missed opportunities for deeper questioning at times during our visit and tour and on understanding the written signs around me. While I can speak some Japanese now as well as read katakana and hiragana, the written language includes more kanji than the basic 50 or so that I know. But despite that, I learned a lot from both our conversation and the non-language dependent visuals.

I was able to take photos of many of the areas that we visited, which I have permission to share here.

Evidence of Production Principles in action – visual systems and 5S

While the leaders at TMH emphasized that they are focusing on the foundational aspects of the Toyota Way such as respect for people and teamwork, the hospital also clearly practices many of the production principles – such as 5S and visual controls – throughout the hospital. For example, in the outpatient clinic, each floor is color coded to make it clearer for wayfinding and organization.

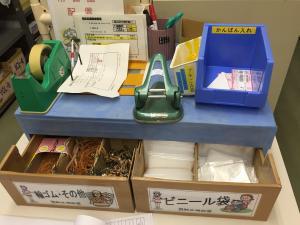

Central Supply – 5S and Kanban

Perhaps the best place to see the production principles in action was in the central supply room

The Japanese culture is one that values cleanliness and organization (the word for “beautiful” is the same as “clean”), but it is does not mean that 5S (a workplace organization system) is natural for the Japanese.

TMH’s central supply area was well organized through color coding, size of containers, and usage. The room was uncluttered and was not actually very big, and kanban cards signaling when supplies were to be reordered were evident throughout the room.

While the organization, color coding, and kanban system are not anything vastly different from systems I’ve seen implemented in hospitals in North America, Australia or one other hospital in Japan, it would have been surprising had Toyota’s hospital NOT had an organized pull-based supply system given that this is one of the foundational principles of TPS.

Of the three other hospitals I’ve visited in Japan, only one used 5S and a kanban systems in local areas – and these concepts were only recently introduced in parts of the hospital at the time of my visit.

Something else that struck me was that the supply department organization and pull process was not highlighted as something special – for example, our host did not say “come check out our great supply area!”

Instead, our host just humbly brought us to the central supply department and let us discover with our own eyes the evidence of the foundational producion principles of “pull” and visual systems in place.

So despite TPS not being practiced to the level that these TPS leaders want, it was evident to me that some aspects of what we consider foundational principles of the production system are second nature at Toyota Memorial.

Other examples of visual controls

Other examples of visual controls were evident across the hospital – such as color coding each floor of the hospital and lines clearly marking where equipment should be. Unfortunately, I didn’t get pictures of all the visual control examples, but there were many.

Electronic visual boards

In the outpatient clinic – on every floor – there were electric boards visually displaying wait time and other information for patients. I wasn’t able to read all of the boards, and the screens rotated, but Mr. Yoshino explained that they were showing information for patients in real-time.

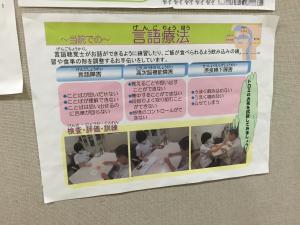

Visual “standard work” for patients

Walking through several of the clinical areas, I also saw examples of “standard work” for patients to visually describe each step of important procedures. I asked about what these signs said and I was told that the purpose was to help prepare patients to understand the purpose and process for their examinations.

Visualization process displayed

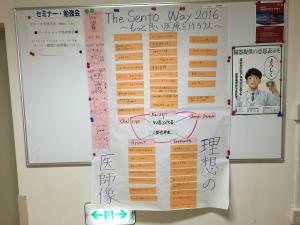

In the hallway outside of the cafeteria, I saw this visual map. I asked what it was about and my host explained that it was a visualization that the new medical residents (who just started that month, as April is the beginning of the academic year in Japan) created in response to the question “What do you think is the ideal vision of a doctor?”.

The call center

I was very interested in the process of the call center, as this was a critical element of Lean process improvement that we did at the Palo Alto Medical Center (PAMF) when we embarked on the Primary Care model line transformation (which James Hereford, Joy Hereford and I wrote about in the Lean Management Journal in 2012).

In the call center, I observed about 15 staff at computer stations answering the phones. I looked around the room with the lens on of what we implemented for Lean management at PAMF’s call center, but didn’t see any of the artifacts of what I might have expected, such as management visual boards displaying current metrics, or signals (at least any visible to me) of when operators needed help).

I asked Mr. Yoshino to ask my hosts about how the manager manages the process. I was told that there are visual cues on the computers, which the operators use to set up appointments in real time, if operators needed assistance. He also shared that the call center was managed by a second party, and wasn’t under direct management responsibility of Toyota Memorial. We moved on before I could ask more follow-up questions.

Patient Waiting Areas

I don’t have any pictures of the clinic waiting rooms, but I was impressed by what I saw.

It wasn’t the color coding of the halls or the vast areas for waiting (both of which were evident), but rather that the waiting areas were nearly empty!

Packed waiting rooms are the norm

This was a huge contrast to one of the other most “Lean” hospitals, Aso Iizuka Hospital, that I have visited in Japan where I was surprised by the huge crowds of people waiting on every floor of the hospital and outpatient clinic areas.

In my post about that Lean-practicing hospital I learned that in Japan, generally patients are not given specific appointment times, but rather general appointment times and that long waits were expected and customary (this has been confirmed by conversations with many hosptial administrators, physicians, and patients in Japan).

As I wrote about my visit to Aso Iizuka, the process in Japan is that usually:

….you don’t get an appointment for your first visit to a doctor. Instead, you go to the clinic (often located within the hospital) and show up with your issue, sort of like an urgent care.

Or if you have a referral by another physician and are able to get an appointment, you are given an appointment for a one hour block of time in which 20 other patients also have an appointment.

Specific appointment times resulted in less waiting

I asked my TMH hosts about appointment times at Toyota Memorial. They told me that patients are given a specific outpatient appointment time and that that they are trying to change the atmosphere of the hospital and expectations of patients for long wait times. Clearly they have been successful!

This move to specific appointment times is something that other healthcare organizations in Japan can learn from!

It would have been better if TMH had built smaller waiting rooms when they built the new facility 12 years ago, but this is an improvement in the overall process of huge wait times in Japan.

Thank you Harold Archer for posting this question on LinkedIn for me to make sure to ask.

Opportunity for improvement

On our tour, I also saw several opportunities for more production principles to be applied. For example, we got to see their new Cyber Knife (the first location to own this advanced technology in Japan). The manager of the area and a technician showed us the CyberKnife operating room and answered some of our questions.

The problem: underutilization of expensive equipment

This piece of equipment that cost roughly US$6million is only in use for 6-8 patients per day. There is a lot of downtime on the machine, which the manager recognized when I asked some probing questions about how often the machine is in use.

My host explained that TMH and the manager knows that their challenge is now to figure out how to 1) get more patients in who could benefit from the machine and 2) determine how to schedule appointments to maximize the up-time of the machine.

The process to solve the problem: leverage the problem solving skills of your people

He explained that it is the manager’s job to take this challenge and to figure out how to solve it – with the organization’s support (sounds like the foundation of people that they had explained to me earlier!).

Given TMH’s emphasis on people development and problem solving, I’m confident that the CyberKnife area manager is working on this problem (and probably in the form of an A3). He may need to run some experiments to understand the market and how to set up his operations, but I anticipate that if I come back in a year, that he will have made significant progress on utilizing this valuable (and expensive) asset, and getting access to more Japanese patients who would benefit.

What about the process of continuous improvement?

It was a packed four hours of learning and discussion at Toyota Memorial!

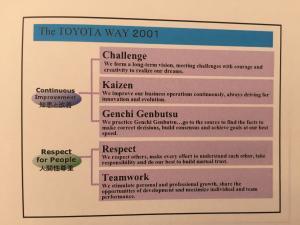

At the start of the day, my hosts spent a lot of time talking about the Toyota Way, particularly about the foundation of “respect for people”. But what about the other core aspect of the Toyota Way: “continuous improvement”?

Following the tour of the hospital, we sat down for one more hour with Mr. Sumiya who shared more information about TMH’s system for problem solving – including patient and staff engagement.

In addition to what I’ve already shared, I learned more about how the leaders at Toyota Memorial think about continuous improvement, including kaizen, hoshin kanri (strategy deployment) and management’s role in problem solving, and will be sharing it in an upcoming post.

If you want to all the posts in this series about Toyota Memorial Hospital, you can find them here:

- Japan Gemba Visit: Toyota Memorial Hospital – Part 1: the most “Lean” hospital in Japan

- Japan Gemba Visit: Toyota Memorial Hospital – Part 2: “Our human resources are our power”

- Japan Gemba Visit: Toyota Memorial Hospital – Part 3: Production system principles in action

- Japan Gemba Visit: Toyota Memorial Hospital – Part 4: Set challenging goals & engage patients and staff in continuous improvement

- Japan Gemba Visit: Toyota Memorial Hospital – Part 5: The role of managers and physicians in leading improvement

Learn more and share

If you are intersted in learning more about how 5S is practiced in Japan, I will be writing a lot more about it soon. I’m leading a tour next this Friday to a Japanese town named Ashikaga where over 150 organizations in the community practice 5S as a uniting leadership and employee engagement strategy.